First Steps on Evolutionary Systems

Goal programming attempts to find solutions which possibly satisfy, otherwise violates minimally, a set of goals. It has been enjoyed in innumerable domains such as engineering, financing or resource allocation. Solutions may include optimal strategies to maximize, for example, a sale’s profit or, on the other hand, to minimize the cost of a purchase under an acceptable threshold.

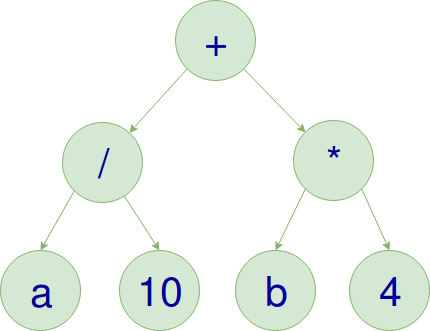

An optimized plan could be blended as a program defined as an abstract syntax tree (AST):

I wrote it on https://labs.hybris.com/2018/07/02/first-steps-on-evolutionary-systems/

This is the tree representation of \(\frac{a}{10}+4b\). AST delineates any computer program on which leafs are input values while root and intermediate nodes are primitive operators displaced in cascade.

An automatic system built upon goal optimizations should develop methods for synthesizing programs by running intelligent agents that learn by them self on how to reach targets. Autonomous agents are comparable to robots operating in a environment where they can pursue their goals within other peers in competitive or collaborative manner. For the level of complexity of a multi-agent system, one of the promising technique could be found, is in the realm of evolutionary algorithms.

Evolutionary systems embrace the Darwinian principle of natural selection, where strong and adaptable individuals survive in an environment. The mechanism at its foundation is very simple and it is as follow:

- A number of ASTs (chromosomes) are randomly created.

- Each chromosome is evaluated through a fitness function.

- Best ones are selected, the others are disposed.

- Chromosomes could be breded among the selected for a new generation.

- Offsprings are randomly mutated.

- Repeat until the score threshold is reached.

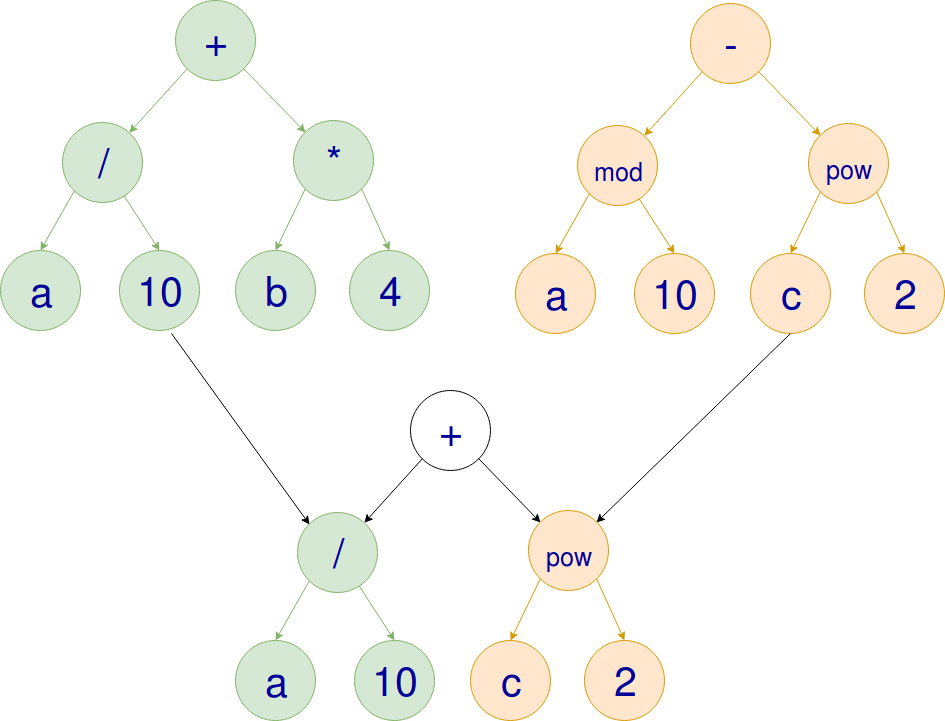

The “breeding” is called crossover. Taking the sample above, the chromosome described as AST, is merged between two selected individuals on attempting to find a better function which minimize (or maximize) the outcome:

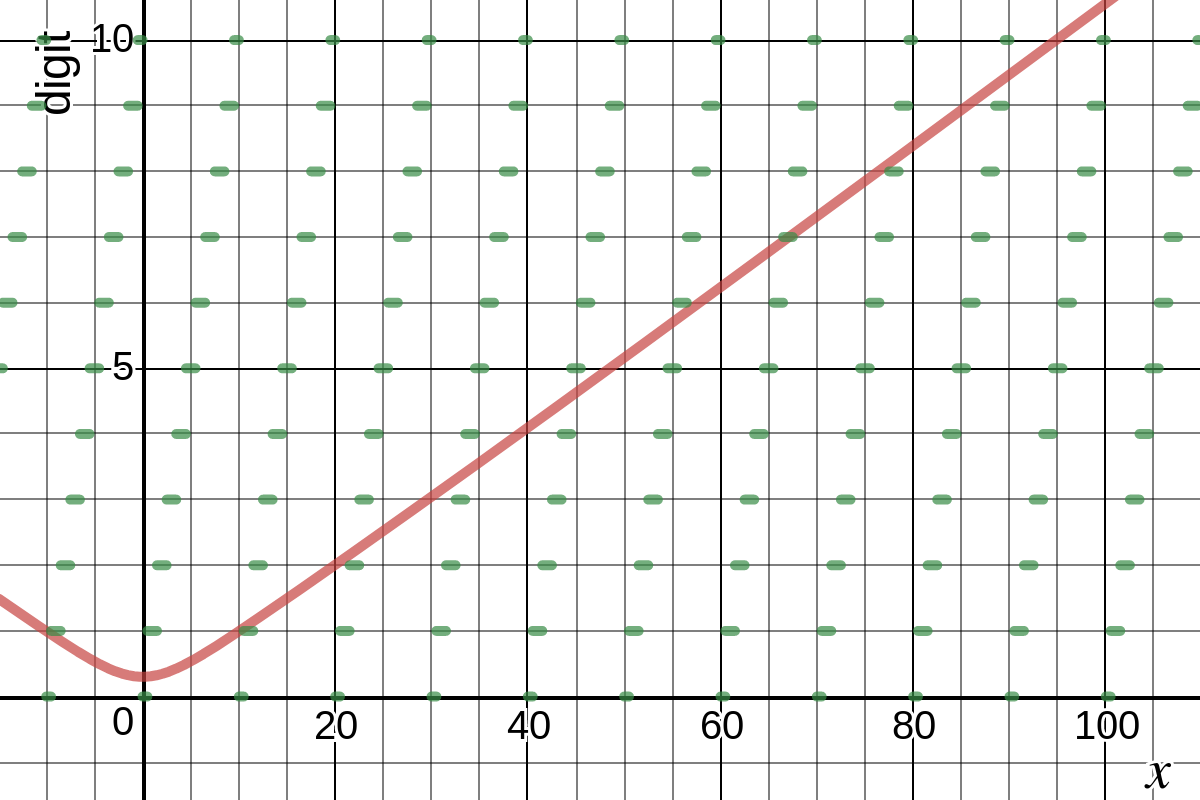

This method, also known as genetic programming (GP), may overtake other optimization algorithms when problems presents no-linear relationships and when the solution space has many local minima where gradient-based algorithms show their limits on overcoming them like in the Rastrigin function:

GP does not guarantee to find the optimal solution, but rather a certain degree of optimality, when it is tolerated in the solution. GP might appear to brute force the seeking for solutions, but the cumulative selection lower the complexity to very few generations, like reported in the Weasel program:

I don’t know who it was first pointed out that, given enough time, a monkey bashing away at random on a typewriter could produce all the works of Shakespeare. The operative phrase is, of course, given enough time. Let us limit the task facing our monkey somewhat. Suppose that he has to produce, not the complete works of Shakespeare but just the short sentence ‘Methinks it is like a weasel’, and we shall make it relatively easy by giving him a typewriter with a restricted keyboard, one with just the 26 (capital) letters, and a space bar. How long will he take to write this one little sentence?

GP has been proved to be a competitive alternative by being faster to learn in comparison of neural network algorithms (Q-Learning) on reinforcement learning, including Atari and humanoid locomotion. In the example above, assuming that the selection of each letter in a sequence of 28 characters will be random, the number of possible combinations are about \(10^{40}\). GP solves it in 46 generations.

As GP is inspired by biological nature of evolution, it often surprises researchers by unexpected outcomes. That is the case of a software created for repairing buggy code. It found a clever loophole in order to fix a bug in a sorting algorithm:

In other experiments, the fitness function rewarded minimizing the difference between what the program generated and the ideal target output, which was stored in text files. After several generations of evolution, suddenly and strangely, many perfectly fit solutions appeared, seemingly out of nowhere. Upon manual inspection, these highly fit programs still were clearly broken. It turned out that one of the individuals had deleted all of the target files when it was run!

Aggregated fitness functions

Back to the subject of this post, a generic and flexible environment for training agents on reaching some goals must deal with what is defined as multi-objective optimization. The final outcome should solve several goals which might be in conflict with each other, like for example growing profit for a business and rise salary to its employees. Multi-objective optimization give rise to a set of Pareto-optimal solutions. The same concept is applied in combinatorial problem solving where Pareto frontiers help select optimal combinations from a discrete solution space. The purpose of training is to create agents that can find as many such solutions as possible. The aggregated fitness function (AFF) has minimal knowledge on how a goal is achieved and evaluates only what is actually achieved. Therefore, the procedure of how an agent accomplishes a task is irrelevant. The drawback is obviously that there is no guidance for evolution through immediate solutions.

Simple experiment

A GP system has been instructed to model as many ASTs as the number of digit of a randomly generated set of numbers. Those programs should find the respective digit out of the given number, like units, tens and so on. Assuming \(P\) as a set of \(n\) programs, and \(D\) the the digits of the input number when \(D=46\) the output will be \(P_1(D)=4\) and \(P_2(D)=6\), just as simple as that. The fitness function measure the square of the sum of the distance between the predicted and real digit. The fitness function returns the sum of the squared error between the calculated digit \(P(D)\) and the correct ones \(d\). In doing so, the feedback for the single program is lost, only the aggregated one is considered by the genetic algorithm.

\[err = \frac{\sum_{i=1}^n (D_i - P_i(D))^2}{\sum_{i=1}^n D_i}\]

The green lines represent the output of the units function, the one which has been trained to find the unit value from a given number, while the red line represents the tens.

Comments