Adaptive Programming Systems for Humans and AI

In the BBC series “How Buildings Learn”, Stewart Brand discusses how buildings evolve over time and, in particular, what distinguishes good buildings from bad ones. One way to answer that is to look for commonalities among those still standing centuries after their construction. Excluding natural disasters like earthquakes, poor quality of materials and construction techniques, or the possible decline of the locality, the longevity of buildings depends on the satisfaction of their inhabitants in maintaining them. How can a static structure satisfy generations of owners? We might be tempted to think that the initial purpose of a building should not vary much over time due to its immutability. That would be correct, but only if we do not include the human element in the equation. Unlike buildings, people move and engage in all sorts of activities. The dynamism is brought by the users, and as expected, it changes over time. It turns out the longevity of a facility is determined by how easily it can meet new demands, and those demands are dictated by the kinds of interactions people have with the building during their activities.

The analogy can be applied to software applications. Comparing the average lifespan of a building with that of a software application, the impact of adaptability is more evident. Applications are disposable and prone to continuous updates, and cases of legacy systems remaining untouched after decades are as rare as anecdotal. Software is built to let users achieve specific goals. As building inhabitants change their uses and, consequently, their purposes and mediators, so too are programs clearly subject to evolution.

Mediators: point of interaction between agents (user, developers and AI generators) and the system. They are affordances such as APIs, design patterns, frameworks, but also GUIs, command lines, etc.

While users interact with the application via its available mediators, programmers leverage a different kind of them offered by the programming system to crystallize the output of their work into a runnable application.

Programming system: Integrated and complete set of tools sufficient for creating, modifying and performing programs. It encompasses programming languages, libraries, frameworks, development environments, and other tools that facilitate the software development process.

The more adaptive a programming system is, the easier it is to apply changes - and at a higher rate - than with less adaptive ones. A flexible programming system is better for the output. If the application is appreciated by customers, change requests inevitably arise, and an important aspect of evaluating whether to build a new application from scratch or update the current one is to consider the potential adaptability to changes. Certain mediators are involved in changing existing software, especially those more inherently tied to the application’s components. We can refer to them as substrates.

Substrates: various underlying mechanisms or interfaces that allow to interact with and modify the software.

Substrates are the layers that encapsulate different modules and environments. They could be related to data management, dominated by the database interface, for example. Mediators may be also volatile archetypes, like prescribed design patterns for software development. When a generic design is found for a recurrent problem pattern, the solution is actually an abstract template for lowering the accidental complexity of the application. That archetype could be seen as a substrate applied to the application for a common problem.

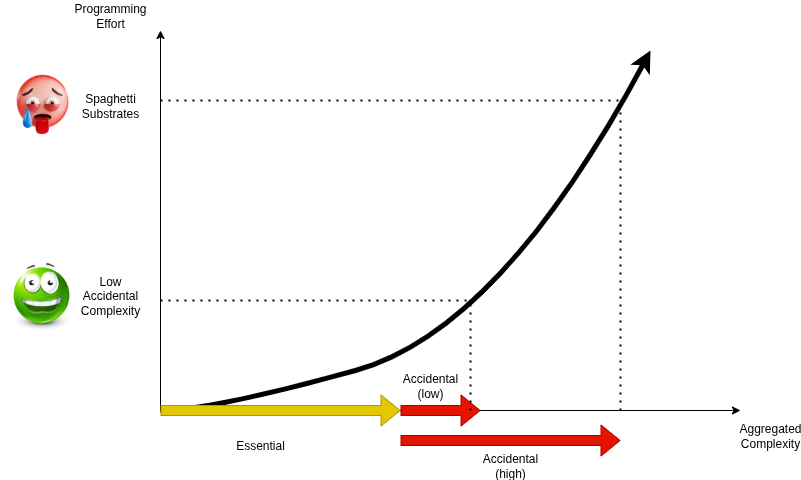

Accidental vs Essential complexity: if you have ever faced a programming challenge like the ones you may be submitted during interviews, you may have experienced the frustration of not being able to solve it. This is the feeling the essential complexity manifests itself. On the other hand, when the programmer should update an intricated legacy system without documentation, the desperation can easily take over. The sorrow is now related to the accidental complexity, which is the kind of trouble introduced into the ecosystem. The essential is not negotiable, but the accidental must be kept at the lowest level.

Let final users be programmers

Mediators vary depending on the role of the agent. Those accessible to consumers may differ from those engaged by producers, as they are indeed very different. Programmers leverage mediators from the programming system, while end users interact with the application through exposed substrates, like GUIs. This separation is usually irreconcilable. Users may not expect to modify the program they are using. In fact, they have almost no chance to change it by themselves. More adaptability also means open authorship, a principle that empowers different roles to modify the software from lower-level substrates than those reserved for using it.

Real cases of open authorship

Are there any live examples of open authorship out there? If you are reading this article, you are probably doing so through a browser. You can open the menu, access “developer tools,” and inspect the page. If you have a bit of HTML knowledge, you can modify the page directly. Pay attention to the page itself, because changes are instantly reflected in the rendered view. The HTML substrate is accessible and modifiable, and the feedback is immediate. A browser lets the consumer be a producer to some extent at the same time. Spreadsheets are another example of open authorship. The grid is visually accessible, and the engine works at the cell level. Users can modify the data and the formulas, and results are promptly reported. Moreover, the formula substrate is hierarchical, as formulas can be encoded at different levels of capability, from simple domain-specific languages to more complex languages like VBScript or Python.

What’s programming?

Empowering users to modify software without the help of professional developers is a way to make it more resilient to the changes that occur over time and to extend the application’s longevity. As mentioned before, this can’t be achieved by eliminating the essential complexity of the problem. The user - whether programmer or empowered user - necessarily needs to understand the problem first and then implement a solution. As Einstein said, “95% of the time is spent understanding the problem; the little rest is on finding the solution”; the essential complexity is the critical part that programming must address first.

For human agents, programming is a logical task, not a language-based one. The brain is not just parsing text when interpreting a program. Rather, it is actively simulating the program’s behavior, following its logical sense and interpreting the effects. It’s quite a different cognitive process than following a text or a flow of thoughts. This may be why a fully committed programmer may exhibit contrasting language attitudes - as vague stereotypes circulating around nerds may confirm.

Evidence of the logical nature of programming can be seen in the tools usually offered by programming systems. Debuggers, code highlighting, code formatting, and other visualization tools are aimed at not exceeding the memory span and to focus user’s attention where it really matters. Those tools are designed for lowering the cognitive load of the mental module charged with the programming task.

What about AI agents? Is their path toward code generation similar to human programming?

Large language/reasoning models (LLRMs) show excellent results in many different tasks, demonstrating a general intelligence, but with uneven performance. To put it simply, LLRMs are essentially next-token predictors, trained to provide a probability distribution of what comes next in a given sequence of symbols. I’m afraid, it is evident that the answer to the previous question is negative. LLRMs are not even close, in abstract terms, to the way humans program. This is not, per se, an insurmountable problem; it just helps to understand why some problems may occur when using those agents to generate code. Recurrent complaints with LLRMs are summarized as follows:

- Struggles with mutable states and side effects. Imperative programming languages are more prone to induce errors in AI agents due to the increasing burden of tracking the state of a program while it operates.

- Shallow code understanding. LLRMs focus on the syntax and semantics of parts of code (like variable names) and less on the overall logic of the program. For example, obfuscated code causes AI agents to fail even on simple problems.

- Problems with multi-step reasoning. This is a generalization of the first point.

- Generates complicated code. LLRMs tend to produce convoluted code, increasing rather than lowering complexity. I guess this problem is due to the already high accidental complexity of the ecosystem, forcing automatons to fill in the boilerplate with even more glue code.

- Fails to meet requirements. Generators do not implement the set of prescriptions in their entirety and refuse to implement them despite repeated requests.

- Despite different prompts, it generates the same code.

- Despite the same prompt, it generates different code.

All-in-one Development Environment

Some difficulties are remarkably similar to those encountered by human developers. Points (1), (3), and (4) are related to the inherited ecosystem and its idiosyncrasies. When it comes to the irrelevant and harmful composition of poorly designed substrates, the burden of keeping them aligned rises exponentially. Misaligned substrates are the source of impedance mismatch that necessitate further sub-problem elaboration specific to the amount of glue code involved. This affects not just humans but automatons as well.

Impedance mismatch: it refers to the difficulties when different system with incompatible data models need to interface with each other. For example, the object-oriented data model in Java clashes with relational model and with the interface (SQL) used in databases.

Unified Mode of Programming

To mitigate the problem, the goal is to build a platform using a minimum number of technologies, glued together in a programming system that allows the definition of a multitude of paradigms by adopting only a single way of expression: a core language sufficient to formalize data, computation, and external service access. This universal language should coherently allow many problem representations, minimizing the accidental complexity that derives from using non-unified integrated development systems.

I began this post by stressing the importance of adaptability for software success, and I can’t end it without mentioning an aspect of the low-code programming paradigm. In particular, if it is important to lower the cognitive barriers for expanding the pool of agents who can be actively involved in changing the tools they are using or creating, then those languages should be elastic enough to allow new versions of themselves specific to a domain (domain-specific language or DSL) while keeping unnecessary code away. A common feature of successful low-code languages is the capability to be changed by agents solely by using the language itself. This is the principle of self-sustainability.

Self-sustainability refers to the extent to which a system’s behavior can be changed from within itself, without having to step outside to a lower implementation level. A programming system that embraces self-sustainability allows its inner workings to be accessible from the user level, usually through macros, which are snippets of code that generate other code.

There is no conclusion to this post, this is just the part of the journey towards understanding what programming is and how to match humans and AI in a common adaptive ecosystem. Giancarlo Frison

- Basman, A., Tchernavskij, P., Bates, S., & Beaudouin-Lafon, M. (2018, April). An anatomy of interaction: co-occurrences and entanglements. In Programming’18 Companion - Conference Companion of the 2nd International Conference on Art, Science, and Engineering of Programming, Nice, France (pp. 188-196). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3191697.3214328

- Clark, C., & Basman, A. (2017). Tracing a Paradigm for Externalization: Avatars and the GPII Nexus. In Companion to the First International Conference on the Art, Science and Engineering of Programming (Programming ’17) (Article 31, 5 pages). ACM. https://doi.org/10.1145/3079368.3079410

- Jakubovic, J., Edwards, J., & Petricek, T. (2023). Technical Dimensions of Programming Systems. The Art, Science, and Engineering of Programming, 7(3), 13. https://doi.org/10.22152/programming-journal.org/2023/7/13

- Petricek, T. (2022, April 28). No-code, no thought? Substrates for simple programming for all.

Comments