Hybrid AI for Generating Programs: a Survey

Computer programming is a specialized activity that requires long training and experience to match productivity, precision and integration. It hasn’t been a secret for AI practitioners to ultimately create software tools that can facilitate the role of programmers. The branch of AI dedicated to automatically generate programs from examples or some sort of specification is called program synthesis. In this dissertation, I’ll explore different methods to combine symbolic AI and neural networks (like large language models) for automatically create programs. The posed question is: How AI methods can be integrated for helping to synthesize programs for a wide range of applications?

Hybrid AI brings together two very different approaches: symbolic AI, which works like traditional programming with rules and logic, and connectionist AI, which relies on neural networks, where large language models (LLMs) being the most advanced example. In this dissertation, I review some literature that tries to combine these methods to leverage their strengths for generating programs. I focus on the most interesting and useful papers, setting aside those that were less clear or relevant. While this overview may simplify some aspects or overlook certain details, my aim is to clarify the key ideas and highlight what has been achieved so far in making these two approaches work together.

Program synthesis (PS) is the automatic process of generating programs that accomplish specified objectives. A program consists of a set of instructions written in a formal language a symbolic engine can interpret and execute. Because of that, programs must be exactly right to achieve the intended outcome otherwise any deviation may lead to incorrect results or even the impossibility to run the program. The central challenge is the transformation of input - which often looks very different to the final program - into working code. The input may take different forms, as pointed below.

You can also Download the PDF version of this dissertation

Input as formal specification

The requirements might be written in a formal language, like test cases in the same language of the generated code or a even more abstract logical form. This is typical of the SyGus 1 challenge, where specification are runnable code snippets.

An example of PS specification states the constraints of the new function max2, its signature and the tests for correctness:

;; The background theory is linear integer arithmetic

(set-logic LIA)

;; Name and signature of the function to be synthesized

(synth-fun max2 ((x Int) (y Int)) Int

;; Declare the non-terminals that would be used in the grammar

((I Int) (B Bool))

;; Define the grammar for allowed implementations of max2

((I Int (x y 0 1

(+ I I) (- I I)

(ite B I I)))

(B Bool ((and B B) (or B B) (not B)

(= I I) (<= I I) (>= I I))))

)

(declare-var x Int)

(declare-var y Int)

;; Define the semantic constraints on the function

(constraint (>= (max2 x y) x))

(constraint (>= (max2 x y) y))

(constraint (or (= x (max2 x y)) (= y (max2 x y))))

(check-synth)

Programming by example

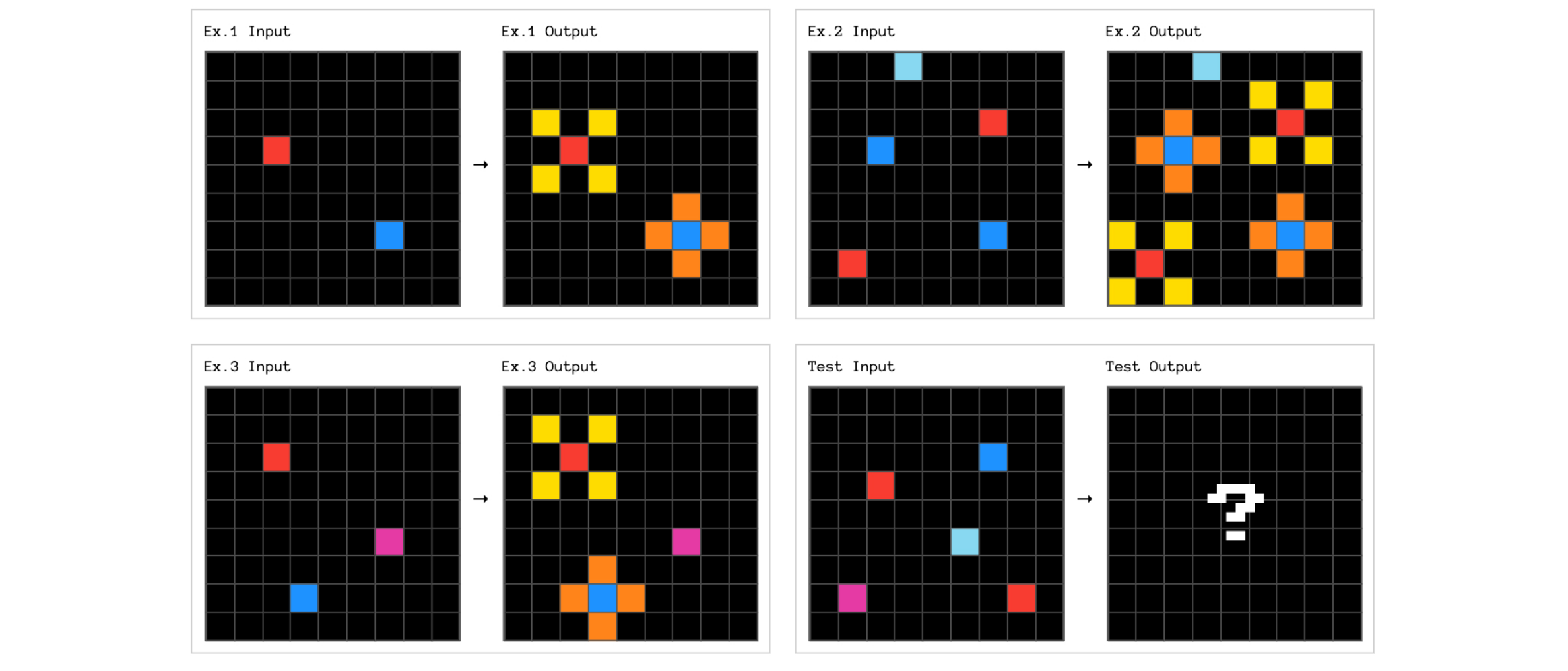

Rather than providing a strict set of requirements the program should adhere to, the generator is tuned on few pairs of input$\rightarrow$output as training samples and then the learned pattern is applied to a unpaired input.

One key detail: the output in these examples isn’t the actual code itself, it’s rather the result of running the target program, and PS succeeds if the generated program produces the same output of the expected one. This type is named programming by example (PBE) and it is the approach adopted for example by ARC-AGI, an initiative for testing human-like intelligence in software agents2.

Input in plain English

These inputs may take the form of high-level specifications written in natural language, such a brief description of what the program should do. An example is the ConCode3 dataset, where pairs of description and code allow the training of PS’s generators from English statements. Using natural language for defining programs has been indeed one of the hardest type of input to work with. The problem is that human language is ambiguous and fuzzy, while code needs to be exact, almost mathematical in its structure, as clearly stated by Dijkstra:

using natural language to specify a program is too imprecise for programs of any complexity4

The lack of rich and complex language models has been a barrier for this type of synthesis, but with LLMs it is possible to capture nuances that were previously out of reach.

Domain specific language

The generated program might be encoded in some general-purpose language that is designed - as the name suggests - to cover a very wide range of tasks. However, PS is usually tailored for narrowed domains where the language expressiveness is not the biggest advantage. This why a domain specific language (DSL) is usually more appropriate.

A DSL brings some other advantages to the process. First of all, a DSL reduces the range of possible solutions a program generator has to search through. DSLs are restricted in the scope and purposes and consequently the search space of possible programs is smaller. In favor of DSL there is also another point: DSLs tend to be more readable for humans. They do not prescribe unnecessary boilerplate code. Rather they keep only the meaningful parts that actually affect what the program will do.

Symbolic vs Statistical methods

Before going deep down to the methods used for PS, I would distinguish three approaches for PS: fully symbolic, fully neural, and hybrid (symbolic + statistical).

Fully symbolic

The exclusive-symbolic systems relies only procedural algorithms for searching solutions that do not comprise any statistical method. Basically, they do not take into account any learned pattern for speed-up the synthesis. Those methods usually fetch the entire search space and when the problem can’t be narrowed in a small number of possibilities, the task might turns out to be very slow or even unfeasible.

Fully neural

On the other end, statistical methods usually count on generalizations offered by neural networks, and thanks to their universal function approximation they tentatively map the input to the final program. Those methods have some drawbacks related to the massive amount of data they requires for obtaining convincing results5.

By their intrinsic nature, purely statistical methods lack of precision that usually is demanded for PS. This is a major issue since the output must run on a formal interpreter. To compensate, post-hoc filtering on multiple program generation is necessary. It consists on generating multiple candidate programs and filter them afterward. Usually it degrades performance with consequent defeat of real-time systems.

Hybrid: combine the best

An attentive observer may notice that the two paradigms above actually complement each other: while neural networks excel at approximations and fuzzy selections, symbolic methods perform best when nesting and composing primitive operations. So why not combine them by exploiting their strengths and mitigating their weaknesses? Hybrid methods attempt to do just that, but since they are fundamentally different, making them work together is not an easy task.

The integration of the two different ways is usually called neuro-symbolic AI (NeSy) and the boundary where one system ends and the other begins varies significantly on the method adopted by the authors. Generally, an appropriate metaphor for NeSy could be the one that emphasize the duality reason/intuition or the more glamoured dichotomy of Thinking Fast and Slow6. It basically describes how well the human (slow) reasoning integrates with the (fast) intuitive mental module. Similarly, in PS the symbiosis occurs for facilitating the search of the target program: the symbolic clockwork scans the possibilities while the neural module suggests the intuitions to search more efficiently.

Enumerative algorithms

What mainly distinguish symbolic from statistical methods is the presence of enumerative algorithms that represent one of the workhorse of the entire program synthesis. Each time the PS generates a candidate program, it is going to be validated in order to ensure correctness with the DSL syntax and the specifications7.

If the verification fails and the candidate does not satisfy the specifications, the system has just found a counterexample – an input on which the program produces an incorrect output that could be added in the history of failed trials for improving search on the next iterations. This is basically the process named counter-example guided inductive synthesis (CEGIS) and it is applied not only on PBE but also on specifications settings.

As previously mentioned, the fast and intuitive module is deployed to guide the search of candidates, but learning to search works best when it exploits existing search algorithms already proven useful for

the problem domain of interest - for example, AlphaGo exploits Monte Carlo Tree Search, DeepCoder uses also Satisfiability Modulo Theories (SMT) solvers. Which kind of searches are usually employed? A distinction should be remarked among different approaches I’ve seen in the surveyed methods.

Top-down enumeration

The top-down paradigm shows how an high-ranking problem could be decomposed in smaller parts that are nested or connected together. In programming, top-down algorithms are the deep first search, it’s companion breath first search or the more generic dynamic programming. Those algorithms are recursive since they unfold into branches that have a similar structure, but they suffer of a big problem.

Many derived branches ultimately prove irrelevant to the optimal solution. If we can infer which sub-problems are worth of scrutiny, we can significantly reduce computation time. This is why we need more sophisticated way than the ones mentioned above. The A* search combines backtracking search with heuristics that helps to find the right path8. Where do heuristics come from? Of course, from a probabilistic learned model. This is the intuition at work! With top-down enumeration, the model could be called just before the search and just once, since its output includes the elements to drive the search without further inquiries.

Because search branches operate independently - a property called Markovian - top-down methods work well for supervised learning. Consider a target output: a program represented as an abstract syntax tree (AST) is essentially a hierarchy of operations that unfold from top to bottom. If we can encode the AST in a neural network, it should somehow reflect inevitably a tree structure we can use to discriminate relevant branches to examine.

Bottom-up enumeration

In contrast, bottom-up searches do not offer the same Markovian characteristic. Bottom-up search builds programs from smaller components, and the correctness or usefulness of a program’s chunk might only become apparent when it’s combined with other segments later in the process.

What might be more appealing in bottom-up settings is that the process of building programs is closely related to the intuition that a human programmer has when he writes small functions first and then combine them to get the desired solution. This differs from the top-down approach, where you start with the big picture and break it down. Instead, bottom-up focuses on solving smaller, manageable problems first and then assembling them into more complex solutions9.

Because the search starts at the bottom of the AST tree and moves its way up, every sub-program it generates is already executable. At any stage of the search, any sub-problem has always a concrete value attached to it, which helps to assess how well it combines with other code segments10.

So, how does the model contribute to the search? Let’s talk about some probability-based methods that help those enumerations.

Probabilistic guided search

Most of practitioners agree that heuristics are useful for finding the right solution, and these shortcuts are based also on observed patterns. In particular, it is evident that not all programs are equally likely - some patterns appear more often than others. There definitely is a bias in the way programs are written. For instance, it is self-evident not a single program use both filter(> x 0) and filter(<= x 0) - that would be simply absurd.

Another suggestion for inferring which operations may be involved comes from an analysis of the training data labels (on PBE settings). Is there some kind of alignment on the output’s elements, for example a sorting? If so, then most likely there is a sort command in the target program11.

Probabilistic grammar tree

Earlier, I exposed some reasons for using DSLs as target programs. One advantage is that DSLs come with a well-defined context-free grammar12 (CFG) which is a formal way to define how languages are structured. A CFG is defined by a set of:

- terminal symbols - those atomic elements that can’t be derived by other elements.

- variables - to be computed by the symbolic engine and rule of productions (non-terminal elements).

- rules of production - the core of the CFG because it is where the generation can unfold the expressiveness of the language and cover myriads of use cases.

The rules determine the language’s expressiveness, allowing it to generate countless use cases. Think of it when forming sentences in English: not every word sequence is valid, and a CFG strictly defines which combinations are allowed. This rigidity contrasts with neural models, which learn from examples and work non-deterministically rather than following hard rules.

Probabilistic context-free grammar (pCFG) is an extension of CFG where each rule is associated with a probability that reflects the chance of choosing that particular rule when expanding the program in a sequences of terminals. Those probabilities (or weights) are statistically derived from a series of programs linked to a specific task13.

Attribute vector

Another way to learn heuristics from training data is the approach used in DeepCoder14 where the system uses a vector to represents the probability of programming features present in the target program. The encoded features depends of course on the DSL adopted for the task. For giving some examples, it might be present features such as:

- unary math operations - like

abs,sqrt. - binary arithmetic - like

+,-. - sequence helper methods - like

head,tail,take,drop. - set functionalities - like

intersection,union,diff. - filters - like

>,<=,==. - tailored compositions of functions - like

mergesort.

The (probabilistic) attribute vector is then used to elicit discriminatory decisions when the enumerator searches for viable solutions.

Argument selector

The two type of statistical models above fit greatly with top-down search since they capture the overall structure of the target program. In contrast, systems such as CrossBeam15 take a bottom-up approach. Instead of reasoning from the top level, the model decides how to combine previously explored operations to build new program components.

As we have seen, not only the programs are kept in history but also their execution result. In this way, in the following iterations those program/value pairs are then used to generate more complex candidates, until the desired solution is found. In this way, promising combinations are prioritized rather then exhaustively enumerate all possibilities.

Branch selector

In the neural guided deductive search (NGDS)16 the model is intended to rank potential extensions of a partial program. It takes the input-output examples and the current candidate program, then assigns weights to different branches the search algorithm could explore.

At beginning, the candidate program is of course empty, and from there starts the divide and conquer top-down approach by building the solution step-by-step from the root of the AST. When the enumerator reaches a branch, the model suggests the most promising path to follow - guiding the search toward a valid solution.

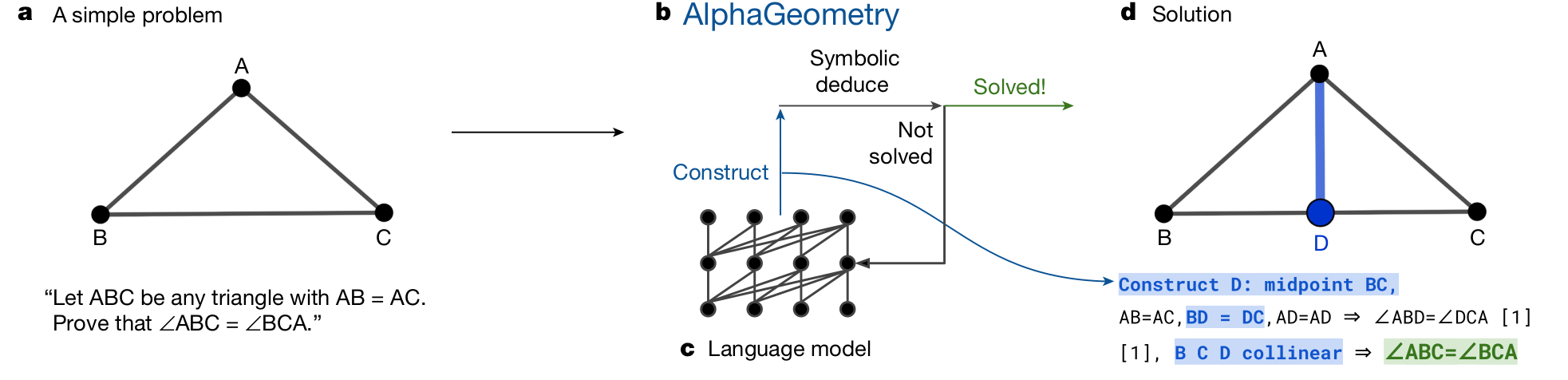

Auxiliary construction

What if the neural model doesn’t just help to speed-up the search by giving proper heuristics, but rather it generates new supporting information, helping the symbolic engine to discover a better path to the correct program? This is what has been proposed in Alpha Geometry17 with the purpose of creating proofs to verify geometrical theories18.

LLMs in the loop

Unlike specialized statistical models, LLMs can bring broader cognitive abilities to PS. Though they were designed to generate the next word in a sequence, they have shown surprising reasoning capabilities, the ones that can be valuable on generating code.

Whether LLMs genuinely reason or they just emulates it by retrieving training data is still controversial19. But for practical purposes, I’m more interested on observing what they can actually do, and integrating them into PS poses new challenges - as any new emerging technology.

Lack of consistency

A persistent challenge is the lack of consistency and generalization in reasoning behavior. The inconsistency arises when LLMs provide different answers to semantically equivalent input. For instance, simply altering the prompt’s tone - or even adding threats to the request - can significantly steer the LLM’s output. This suggests that LLMs probably don’t have a stable, logical framework guiding their answers.

Crafting effective prompts remains an art (maybe yet one of the fewer exclusive to humans?) and this unpredictability adds another layer of uncertainty to PS. Indeed, this kind of problem is well known to practitioners, and when a problem is familiar, there are usually ways to circumvent it, as those surveyed here.

When LLMs generate programs - and usually they return many wrong solutions - the correct solution is most often in the proximity of the wrong ones, and that, by searching in the neighborhood of the invalid proposals, we may be able to guide the search to find a solution faster by compiling a pCFG as described in a previous section.

Context is the king

LLMs being based on the transformer architecture possess long-term memory that enables to track distant elements in the request. This capability joint with vast ground knowledge that extends the mere narrow scope of the PS’s request, is indeed helpful on determining proper variations on the generated program.

As memory capabilities are present in more simpler neural architecture, in LLMs they surely reach undisputed highs. This aspect affects also the latent-space that governs the network capabilities. LLM’s embeddings incorporate much more information than in older neural architectures. RAG (retrieval augmented generation) is a method to encode vectors for enabling similarity search on very complex structures. Though similarity is indeed used for fuzzy searches, its importance on PS remains marginal due to the more tight requirements for generating programs. Program structures are closer to graph representations that hardly can be generated only by similarity means.

The leverage of high contextualization is well exploited in top-down search methods where an hierarchical view of the final goal gives an important help on splitting high-level problems into tiny ones. On the other hand, this reliance on context can become a drawback when using those powerful models for bottom-up searches. Starting from the big picture and trying to work backward, from basic functions to complex solutions, is much harder.

Hybrid methods

Alpha Geometry

As just previously mentioned, the intuitive hint comes from a neural model based on the transformer architecture. It is initially pre-trained with a large amount of synthetic-generated cases of pure geometrical deductions to create a grounding latent space for geometrical knowledge. Then the model is fine-tuned on a generating auxiliary statements to be added to the initial geometrical proposition20.

DeepCoder

Or how to learn to write programs with a NeSy approach. It is based on PBE and it employs a neural network (no LLM) to encode an attribute vector that list the features the final program should include. The search will start by including the most promising features and it will test-and-prune inapplicable programs till it finds a solution that satisfy the examples provided21.

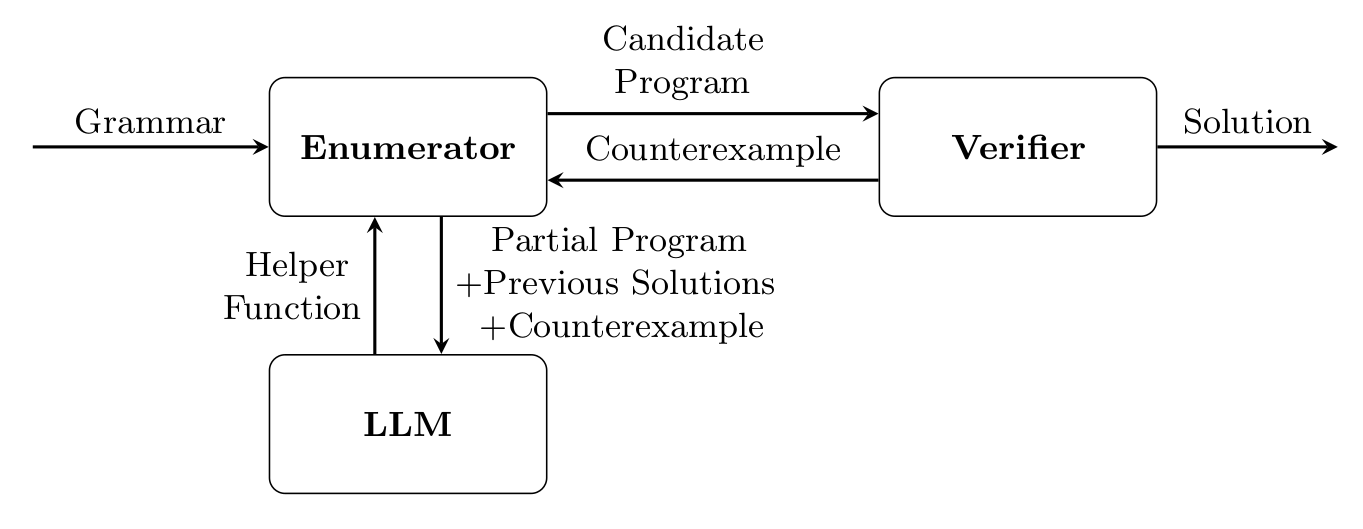

iLLM-synth

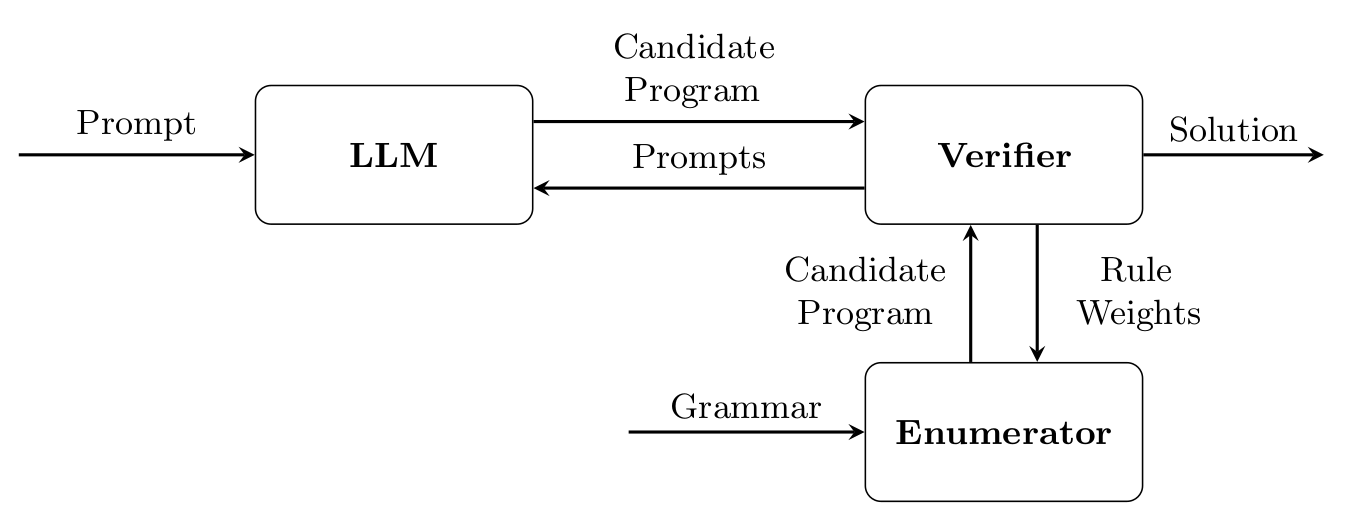

This method involves prompting the LLM to provide helper functions or syntactic suggestions based on the partially constructed program and any counterexamples encountered (CEGIS) and the provided problem specification (SyGus). The LLM’s feedback can even augment the grammar and update rule weights dynamically as the search progresses. A pCFG is created from LLM’s suggestions and the Symbolic searcher apply an A* algorithm based on the heuristics calculated in the pCFG. The search stops when a solution is found or a max cost is reached. As cost it is intended as a max depth in the search tree is reached, or the time budget is spent or when the diminishing return of searching does not worth further explorations22.

Neural guided deductive search

It is a PBE oriented method where a DSL provides the vocabulary of the operations that apply in different parts of the input. The method works by filtering the most likely useful operations (via statistical learning) and then chaining them together recursively, following a functional programming style23.

Take for example the following problem: “Firstname Lastname” $\rightarrow$ “FL”:

- The model’s inference breaks it down into smaller problems by splitting them with the

firstWordandlastWordfunctions. - Those two branches are then computed separately by recursively solving “Firstname” and “Lastname”.

- The model finds the operating sequentially

firstCharto the previous operations might lead to interesting results, that the model again will attempt tocombinethem together.

If this sounds over-simplified, well, it is. Real-world cases involve more complexity, but this gives the basic idea24.

Crossbeam

Differently from previous approaches, the enumerative search follow the bottom-up prescriptions. Starting from the raw input, it applies most likely operations and their result will be used in the following iterations. The search is guided by a neural model trained on program examples. While in NGDS the model gives indications on the AST tree, in Crossbeam only the operations’ output is considered for ranking nested operations. The model learns how to combine evaluated sub-programs in a bottom-up manner25.

HySynth

Differently from other methods, LLMs are prompted first to guess what will be the program for a PBE problem. Candidate programs are used to compile a pCFG which will then guide the following bottom-up search.

The search method falls under dynamic programming, meaning it builds the program from its smaller parts step by step, assigning a computational cost at each new chunk of code. This cost reflects the resources needed to execute that part, as well as the search process itself and it is used for filtering out unsuitable candidates. The DP-based search stores intermediate results to avoid redundant calculations, improving efficiency by skipping explored sub-programs26.

Conclusion

In this brief overview I explore how different methods for PS can be combined in flexible way. Various approaches have been tested to find simple and effective ways to generate programs. Pure statistical methods, especially when they are based on LLMs, might provide simple methods that do not requires combinations of techniques but rather they rely on the universality of their broad context they can leverage for producing code.

Usually, fully neural approaches are effective when problems are simple or LLMs can compensate the lack of explicit knowledge in the input, or they can simply exploit massive amount of publicly available programming code. When none of the above conditions applies, LLMs are beneficial when paired with enumerative processes by guiding the search towards more plausible candidates. The intersection between symbolic and neural systems lies where probabilities may have a role on compiling heuristics. In particular, the flat semantic of a DSL can be more valuable for search when enriched with pCFG. author: Giancarlo Frison

-

SyGuS-Org. (n.d.). SyGuS language. SyGuS. Retrieved from https://sygus-org.github.io/language/ ↩

-

Chollet, F., Knoop, M., Kamradt, G., & Landers, B. (2024). ARC Prize 2024: Technical Report. arcprize.org ↩

-

Soliman, A. S. (n.d.). CodeXGLUE-CONCODE dataset. Hugging Face. Retrieved from https://huggingface.co/datasets/AhmedSSoliman/CodeXGLUE-CONCODE ↩

-

Dijkstra, E.W. On the foolishness of “natural language programming”; https://bit.ly/3V5ZP5 ↩

-

Moreover, in many cases those datasets are synthetically generated by the same models adopted for reversing them into programs. Unfortunately, it introduces the self-selection bias, the kind of problem where the training data is not actually a reliable sample of real-case scenarios ↩

-

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ↩

-

This verification should not cause significant performance degradation, as the verifier is symbolic and typically the same component that will execute the generated artifact once deployed in the target system. Unless the verification involves costly data access, we can confidently assume it takes negligible resources. ↩

-

Li, Y., Parsert, J., & Polgreen, E. (2024). Guiding enumerative program synthesis with large language models. Proc. ACM Program. Lang., 8(POPL). ↩

-

bottom-up search is similar to mathematical factorization, which refers to the process of breaking down a number into smaller factors. Given a non-prime number $n$ then $n = a * b$ where $a,b$ are factors of $n$. Important note: it’s easy to multiply, but hard to factor. ↩

-

Shi, K., Dai, H., Ellis, K., & Sutton, C. (2022). CROSSBEAM: Learning to search in bottom-up program synthesis . arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.10452 ↩

-

Balog, M., Gaunt, A.L., Brockschmidt, M., Nowozin, S., & Tarlow, D. (2016). DeepCoder: Learning to Write Programs. ArXiv, abs/1611.01989. ↩

-

The term “context-free” means that the rules for creating a valid sentence depend only on the individual symbols themselves, not on their surrounding elements. Imagine building a sentence with blocks; each block has a specific role regardless of where it sits in the final structure. ↩

-

Those programs might be given training samples but also generated programs as we will see specifically with LLMs adoption. ↩

-

Balog, M., Gaunt, A.L., Brockschmidt, M., Nowozin, S., & Tarlow, D. (2016). DeepCoder: Learning to Write Programs. ArXiv, abs/1611.01989. ↩

-

Shi, K., Dai, H., Ellis, K., & Sutton, C. (2022). CROSSBEAM: Learning to search in bottom-up program synthesis . arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.10452 ↩

-

Vijayakumar, A. K., Batra, D., Mohta, A., Jain, P., Polozov, O., & Gulwani, S. (2018). Neural-guided deductive search for real-time program synthesis from examples. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. Not specified in the excerpt).1 Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.01186 ↩

-

Trinh, T. H., Wu, Y., Le, Q. V., He, H., & Luong, T. (2024). Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06747-5 ↩

-

The reader might find mathematical proofs a bit out of scope with the topic of this dissertation, but the Curry-Howard correspondence equates propositions with types and proofs with programs. That means when we are talking of geometrical validity proofs we are actually describing programs that derives consequences from axioms to the target state ↩

-

Kambhampati, S., Valmeekam, K., Guan, L., Stechly, K., Verma, M., Bhambri, S., Saldyt, L., & Murthy, A. (2024). LLMs can’t plan, but can help planning in LLM-Modulo frameworks. arXiv. https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.01817 ↩

-

Trinh, T. H., Wu, Y., Le, Q. V., He, H., & Luong, T. (2024). Solving olympiad geometry without human demonstrations. Nature. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-023-06747-5 ↩

-

Balog, M., Gaunt, A.L., Brockschmidt, M., Nowozin, S., & Tarlow, D. (2016). DeepCoder: Learning to Write Programs. ArXiv, abs/1611.01989. ↩

-

Li, Y., Parsert, J., & Polgreen, E. (2024). Guiding enumerative program synthesis with large language models. Proc. ACM Program. Lang., 8(POPL). ↩

-

Though it appears to be more a bottom-up, it is still top-down because the process is driven by attempting to satisfy the overall goal of transforming the input to the target output by recursively applying rules from the DSL. ↩

-

Vijayakumar, A. K., Batra, D., Mohta, A., Jain, P., Polozov, O., & Gulwani, S. (2018). Neural-guided deductive search for real-time program synthesis from examples. In Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (pp. Not specified in the excerpt).1 Retrieved from https://arxiv.org/abs/1804.01186 ↩

-

Shi, K., Dai, H., Ellis, K., & Sutton, C. (2022). CROSSBEAM: Learning to search in bottom-up program synthesis . arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.10452 ↩

-

Barke, S., Gonzalez, E. A., Kasibatla, S. R., Berg-Kirkpatrick, T., & Polikarpova, N. (2024). HYSYNTH Context-Free LLM Approximation for guiding program synthesis. ↩

Comments