The Curious Case of Tip of the Tongue phenomenon

Stuck on a name? It’s like having a word stuck right on the tip of your tongue, but you just can’t remember it. Like a ghost, it is driving us toward a right direction with a sense of closeness but without never revealing us the name. Imagine trying to open a door with a bunch of keys, but none of them fit. That’s the tip of the tongue feeling (TOT), and it happens to everyone sometimes.

The TOT state is also difficult to examine, because as you might imagine, it is identified only subjectively and escapes an objective scrutiny. How do we recognize to be in a TOT state? If you are unable to think of the word but you feel sure that you know it and that it is on the verge of coming back to you, then you are in a TOT state1. However, it’s important to distinguish TOT states from a similar phenomenon known as the feeling of knowing (FOK). While during a TOT we have the sensation to be just one step away to pronounce the answer, FOKs emit different feelings. They gives us the resignation that we don’t know the target word, but we can eventually recognize the right answer among some alternatives.

Interested in language? Take a look into basic principles of language

If you feel uncomfortable experiencing a TOT, it would be pleasant to you to know that usually the feeling associated lasts for no longer than a minute, but be aware that half of the times a TOT is never solved. The sensation of being able to retrieve the word is accompanied by clues that usually appear to be correct, such as the first letter2 and even the number of syllables of the target word. Psychologists found that dictionary definitions of uncommon English words would be enough for triggering a word-finding failure in their experiments. That’s why rare words, along with celebrity names, are used so widely in TOT experiments.

While we know all the sensation related to TOT, not all individuals experience this state with the same frequency. Students in their twenties might have one or two per week, while the frequency doubles for elderly people in their 80s. Age disparities seem to be the most correlated trait with this phenomenon, corroborating causal hypothesis that center their attention on cognitive degradation. While it seems a direct and intuitive explanation, this is not the end of the story. We will unfold some interesting reasons behind TOTs.

hypothesis survey

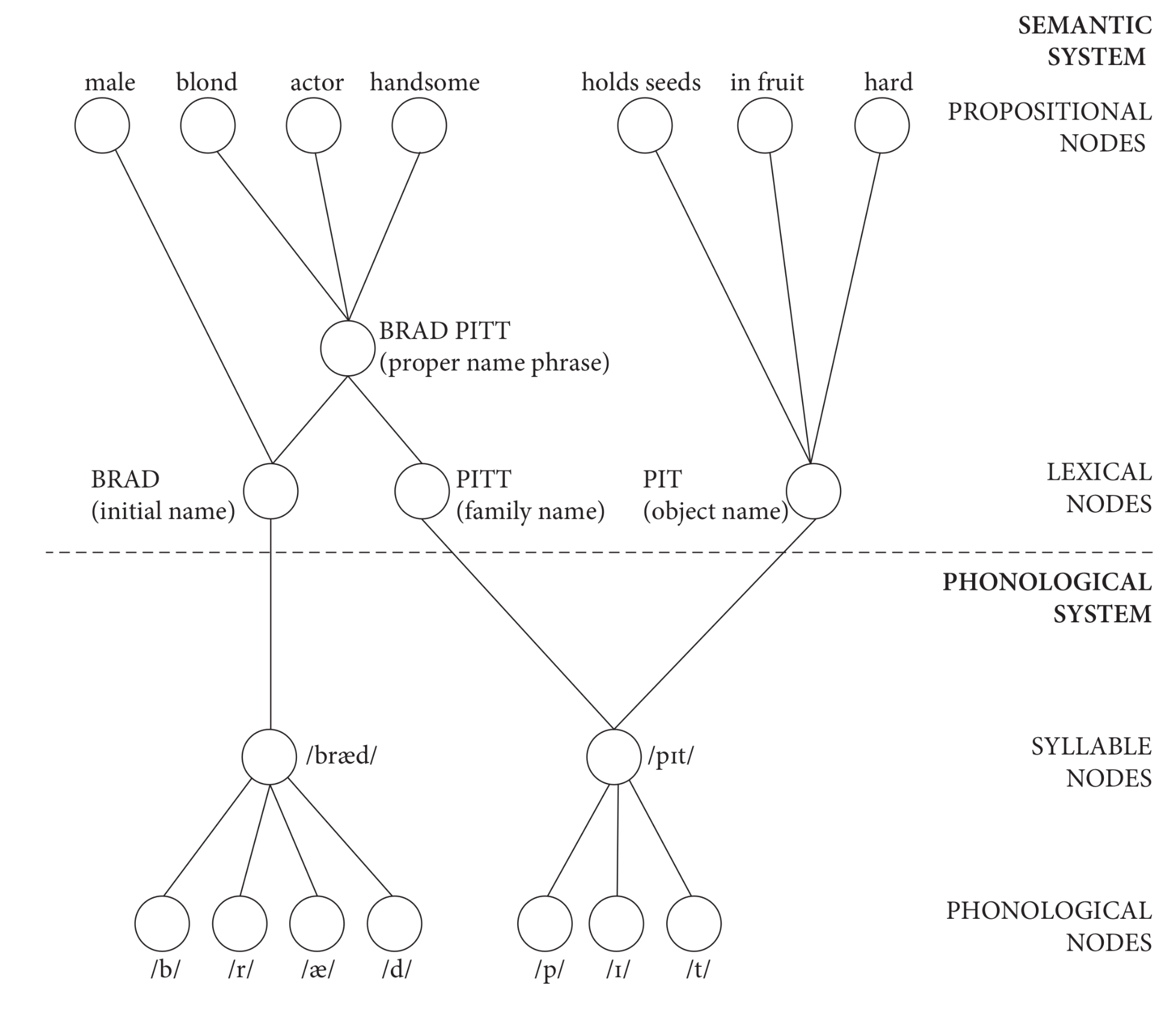

The effect has been under scrutiny since its first mention3 in the 19th century, but while early hypothesis were formulated in the thirties of last century, the TOT state is a prolific arena of research even nowadays. What makes TOT happening? Fingers are pointed against cognitive processes that involve memory and language. In particular, the linking bridge between the semantic memory - dedicated to memorize causal relation among concepts - and the phonological loop, the mental system entitled to vocalize words. How those modules may give us the sensation of TOT?

When we try to remember, the meaning of the word allows direct and immediate access to its sound, thus enabling vocalization. However, sometimes the phonological entry is not fully activated, instilling a certainty of knowing in the absence of expression ability. What could be the origin that causes those impediments between semantic and phonological systems? There are several hypothesis that have been evolved with time.

incomplete retrieval hypothesis

Let’s think of remembering a word. The more clues and reference you have the easier is to narrow down your search. When there are many paths to the final destination - the target word - it will be more likely the retrieval will be successful. Each clue acts as a signpost, pointing you closer to the target word4. According to this idea, if there are not so many paths for finding the right word, it would be hard to solve the search. Therefore, it is a lack of related clues that afflicts the identification of the correct answer. If you find this theory appealing, you might be disappointed by some findings5 that are undermining the validity of this hypothesis as solely responsible of TOT.

In the experiment, participants were fired with casual words exactly when they were experiencing TOTs. Those “bullets” (metaphorically speaking) were either related or unrelated to the target. It happened that unrelated words don’t affect the resolution of the TOT. Instead, related ones have an influence but in opposite way than predicted by this theory: more related words -> less successful resolutions.

blocking hypothesis

The experiment5 above may support a complementary explanation for TOTs. What if some clues instead of favoring retrieval, they prevent it? It is something that Freud mentioned6 when we associate a target name too early during the resolution phase, in the way:

“although immediately recognized as false, nevertheless obtrude themselves with great tenacity”

According to the blocking hypothesis, it is not just that a wrong candidate diverts attention away from the right word, it actually competes against the right target as solution. Related words obstruct the reach of the target. It is this impediment the responsible of holding back good resolutions7.

Similar words have such power that it is not even necessary to provide them directly. Unconscious alternative words that come to mind that are too weak to be recall may be capable of inhibiting target retrieval8 (somehow compatible with the knowledge hypothesis, hold on to the following chapters).

Also the blocking hypothesis present some weaknesses. According to the theory, an higher rate of TOT should be associated with a corresponding higher number of alternative words reported during the TOT state - because the theory prescribes - it is the alternatives that are blocking the target, right? Actually not. A substantial amount of TOTs are reported without any alternative word9. Also in this case, evidences do not clearly support the examined theory.

inhibition deficit hypothesis

It is worthy to mention that another hypothesis is closely related to the blocking hypothesis. The inhibition deficit hypothesis (IDH) emphasize the inhibitory control of speech. According to IDH, the retrieval is successful when we can get rid of all distracting information and reach the target without being overwhelmed by irrelevant details. A TOT state is due to the confusing and distracting amount of extraneous information (This is a more formal term that means not essential or necessary. May sound a bit pedant, but I like this term 😊) that impedes a straight resolution10. In support of this, the capacity of excluding noise during cognitive processes degrades with age. Aged people can less effectively shout out distractors than youngers, explaining why elderly people experience more TOTs than youngers. On the other hand, even this theory is not the whole picture. There is an amount of evidence that shows older adults produce instead fewer alternates during a TOT compared to younger people11. For just this reason elderly people should be affected less, and not more by TOT. Something here does not add up.

transmission deficit hypothesis

This model suggests that TOT states arise from impairments in the communication between various cognitive modules or brain regions, rather than blaming individual systems. The retrieval of phonological traits might be particularly susceptible to linking failures because it is dependent on fragile connections between a word’s lexical node (lemma) and its phonology (Fig. 1). In contrast, the semantic and lexical systems are more connected. That’s why they are more resistant to aging decay than the lexical/phonological linking12.

If you find many similarities with incomplete retrieval hypothesis, you are not wrong. Both point to a lack of strong connections. Interestingly, this is why some neurological evidences that enlighten aging-related issues, support all of them. Older adults exhibit reduced activity in the left insula - probably due to age-related atrophy13 - an important region for phonological production14.

knowledge hypothesis

This idea comes with diametrical different assumptions than the previous ones. It suggests that TOTs aren’t caused by declining brainpower, but by having too much knowledge. When experiments’ results are controlled over the type of target words, something new pop-ups from the data. The author states that in the experiments that do not require proper names (like celebrity names) there is no age difference in TOT rates8. This seems to be a quite incisive discovery.

If we take the transmission deficit hypothesis as granted, more you know about the target word more the semantic system compensate the aging effect. Instead, data shows that higher the knowledge, the higher the TOT rate. This aligns somewhat with the blocking hypothesis, where too many related words might get in the way.

illusion hypothesis

Among the explanations this is the most controversial one. It says that the emotional charge carried during a TOT state is an induced feeling that trigger our curiosity on the target and raise willingness on searching the right word. It seems a mental trick that tell us: “hey, for sure you know the answer, keep going!”, to push us for searching more obstinately. As we can find out in the next chapter, this is not really a disadvantage; rather it is a positive feature of TOT. In situations of great uncertainty this meta-cognitive decision can be helpful on pursuing the right action15. In support of this thesis, it has been found out that TOTs are more frequent in groups. Group magnify the feeling of the target word is on the reach, prompting TOT states more than what occurs on single individuals16.

upsides of TOT states

Remember the “tip-of-the-tongue” feeling? It might be a good thing. As mentioned above for the illusion hypothesis, TOT state is beneficial because it induces more curiosity and motivation to spend more energy to reach an achievement15. Moreover, the confidence of the apparently latent knowledge pushes us into more risky decisions. For example, participants in test quizzes are more willing to risk their grades if they are in TOT state. It turns out that such a bravery is prized by better results15and then the frustrating feelings of inability are somehow balanced by higher performances.

practical applications

This phenomenon open the way to practical applications, for example in the area of assessing students’ knowledge. If they can’t come up with a short answer, they could maybe use TOTs to know when it’s smart to ask for multiple-choice options. Quiz designers might exploit TOT effect to build adaptive tests, to let participant to demonstrate various levels of knowledge, including knowledge that might be present but momentarily inaccessible17.

conclusion

This survey of potential explanations for the TOT phenomenon hasn’t yielded a definitive answer. Instead, the evidence suggests that various hypotheses likely contribute to TOTs, each with varying degrees of influence. Tough not privileging a single explanation, we can de-emphasize the incomplete retrieval hypothesis due to the lack of compelling supporting evidence. The blocking hypothesis, however, might be encompassed by the knowledge hypothesis. Since age-related cognitive decline is a well-established factor, it could not be ignored as contributing factor in TOTs.

more curiosities

There are also some tricks could be used to mitigate those kind of retrieval failures. If the blocking hypothesis affirms that if we can’t discern useful clues from irrelevant noise we are more affected by TOT. So why not consciously attempt to ignore related but incorrect words? As Woodworth (1938) suggested:

…the wrong name recalled acquires a recency value and blocks the correct name … a rest

interval allows the recency value of the error to die away

A curious aspect of TOTs has been found out on the ethical sphere. The sensations associated with TOT is a kind of warm glove that attributes high ethical values to not able to remember memories. Curiously, when celebrities’ names induce TOT states, they are judge more ethical17.

-

(p. 329). R. Brown and McNeill (1966). The “tip of the tongue” phenomenon. Journal of Verbal Learning & Verbal Behavior, 5(4), 325–337. Doi: 10.1016/S0022-5371(66)80040-3 ↩

-

Usually correctly guessed 50% of the times. Rubin, D. C. (1975). Within word structure in the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 14, 392-397. ↩

-

James W. Principles of psychology. New York: Holt; 1890. ↩

-

Wenzl (1932, cited in Woodworth, 1938), R. Brown (1970) ↩

-

Jones, G.V. Back to Woodworth: Role of interlopers in the tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon. Memory & Cognition 17, 69–76 (1989). Doi: 10.3758/BF03199558 ↩ ↩2

-

Freud (1901, cited in Reason & Lucas, 1984) ↩

-

Burke et al., 1988; Reason & Lucas, 1984; Jones, 1989; Jones & Langford, 1987 ↩

-

Burke et al, 1991 - On the tip of the tongue: What causes word finding failures in young and older adults? Doi: 10.1016/0749-596X(91)90026-G ↩ ↩2

-

Reason, J. T., & Lucas, D. (1984). Using cognitive diaries to investigate naturally occurring memory blocks. Everyday memory, actions and absent-mindedness, 53-70. ↩

-

Awh, Matsukura & Serences, 2003; McClelland & Rumelhart, 1981; Ridderinkhof, Band, & Logan, 1999 ↩

-

Burke et al., 1991; Burke & Shafto, 2004; Fraas et al., 2002; White & Abrams, 2002 ↩

-

Cognition language and aging doi10.1075/z.200; Derived from a theory of language production called the Node Structure Theory (MacKay, 1987). ↩

-

Shafto, Meredith A., et al. “On the tip-of-the-tongue: Neural correlates of increased word-finding failures in normal aging.” Journal of cognitive neuroscience 19.12 (2007): 2060-2070. ↩

-

Shafto, Meredith A., et al. “Word retrieval failures in old age: the relationship between structure and function.” Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 22.7 (2010): 1530-1540. ↩

-

Socially Shared Feelings of Imminent Recall: More Tip-of-the-Tongue States Are Experienced in Small Groups - Rousseau, Kashur 2021. ↩

-

The tip-of-the-tongue state as a form of access to information: Use of tip-of-the-tongue states for strategic adaptive test-taking - Cleary 2021 ↩ ↩2

Comments