Short glimpse on predicate and first order logic

Course: Foundations of Artificial Intelligence III

This course spares topics that can be listed in 3 main groups. Propositional logic (PL), first order logic (FOL), reasoning and satisfiability. The literature mentioned in this course refers to Chapters 7,8 and 9 of AIMA book. The example applications used in the course, is (among many other) the wumpus world (inspired by the one in the AIMA book) which is applied as a playground for PL and FOL explanations. Logic as a general class of representations to support knowledge-based agents. Such agents can combine and recombine information to suit myriad purposes. A logic must also define the semantics or meaning of sentences. The semantics defines the truth of each sentence with respect to each possible world. For example, the semantics for arithmetic specifies that the sentence “x + y =4” is true in a world where x is 2 and y is 2, but false in a world where x is 1 and y is 1.

Propositional Logic

PL is a simple language consisting of proposition symbols and logical connectives. Its syntax defines the allowable sentences while its semantics defines the rules for determining the truth (just true or false) of PL sentences with respect to a particular model. The semantics for propositional logic must specify how to compute the truth value of any sentence, given a model. This is done recursively. All sentences are constructed from atomic sentences and the five connectives.

A model is a truth assignment of propositions in a knowledge base (KB) which is a set of sentences (axioms) when the sentence is taken as given without being derived from other sentences. Sentences can be derived from other sentences that are logically entailed. Entailment is the idea that a sentence follows logically from another sentence. In mathematical notation, we write α $\vDash$ β if and only if, in every model in which α is true, β is also true.

Inference

Sentence derivation is done by running an inference algorithm that follows the modus ponens logic paradigm or the modus tollens. The former refers to deductive forward chaining (FC) while the latter the inductive backward chaining (BC) families of algorithms. FC is an example of the general concept of data-driven reasoning; reasoning in which the focus of attention starts with the known data. BC algorithms, as its name suggests, works backward from the query. If the query $q$ is known to be true, then no work is needed. Otherwise, the algorithm finds those implications in the knowledge base whose conclusion is $q$.

Resolution

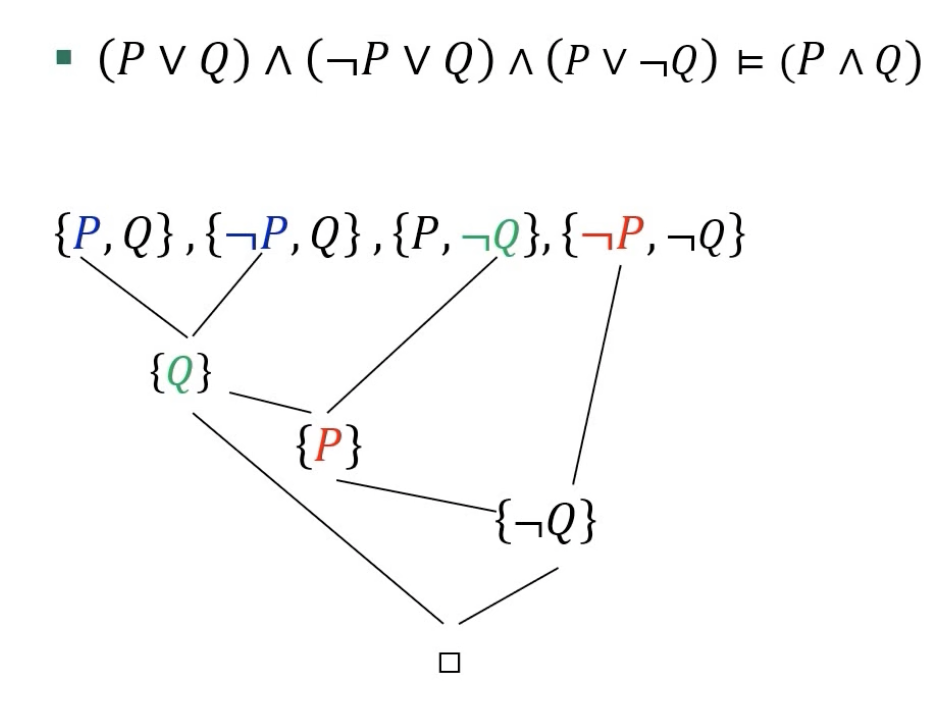

For a sentence to be proved as true, it must be sound and complete. A sentence is valid if it is true in all models. For example, the sentence P ∨ $\neg$P is valid. Valid sentences are also known as tautologies, they are necessarily true. If a sentence is valid and its premises are true, then it is also sound. For being complete, the inference algorithm must derive any sentence that is entailed. Proofing is obtained by reductio ad absurdum (or proof by refutation or contradiction) on which α $\vDash$ β if and only if the sentence (α ∧ $\neg$β) is unsatisfiable. How resolution works for obtaining a proof?

- First, $KB \wedge \negα$ is converted in CNF. CNF stands for conjunction normal form (formula consists only of conjunction of disjunctions).

- Each pair that contains complementary literals is resolved to produce new clauses, until:

- There are no new clauses that can be added, in which case KB does not entail $α$.

- Two clauses resolve to yield the empty clause, in which case KB entails $α$.

First order logic

PL lacks the expressive power to concisely describe an environment with many objects.

The language of FOL is built around objects and relations and it assumes that the world consists of objects with certain relations among them that do or do not hold. While propositional logic commits only to the existence of facts, FOL commits to the existence of objects and relations and thereby gains expressive power. In FOL are represented objects, predicates and functions. Predicates are $n$-arity relations among objects or employed for expressing features of a single object. Functions are expressions that return a single object out of a set of arguments.

In FOL, it is natural to express properties of entire set of objects and it is done by adopting the existential quantifier ($\exists$) and the universal quantifier ($\forall$).

Natural numbers

An interesting application of FOL is the description of Peano numbers which are Peano numbers are a simple way of representing recursively the natural numbers ($Nat$) using only an axiom ($Zero$) value and a successor function $succ(Nat)$.

\(Nat(Zero).

\forall x [Nat(x) \rightarrow Nat(succ(x))].\)

Unification

This is the process to make - whenever possible - different logical expressions look the same by substituting properly the value of variables. With unification it is possible to construct all queries that unifies with a given sentence, e.g.: $Employes(SAP, Giancarlo)$ and $Male(Giancarlo)$ some queries might be: is there are male employee in SAP? In FOL it might be: $\exists x [Male(x) \wedge Employes(SAP,x)]$ .

Reasoning in FOL

Reasoning in FOL works by bringing the formula into Skolem form - by removing existential and universal quantifiers - and transform it in clause normal form (which indicate a formula composed of conjunctions separated by comma). Use propositional reasoning (resolution, SAT), forward cha backward chaining.

Herbrand universe

The Herbrand Universe (HU) is a set of combinations of all ground terms (not variables) present in a formula, e.g.: in the clause formula $CapitalOf(x,y) \rightarrow IsA(x,City), IsA(y,Country), PartOf(x,y)$ we have the HU as $HU = {City,Country}$ but if there would be a function, the HU size will be infinite. The HU is useful for example to restrict the search space of Prolog programs, whenever it is possible.

The HU could play a part on resolution in FOL by applying the Herbrand expansion which is the set of formulas the results of substituting terms in the initial formula in all possible ways. Given a knowledge base: $KB = \forall x [SpecialAgent(x) \rightarrow SpiesOn(x, Danz)] \wedge SpecialAgent(MrSmith)$

it will be translated as “every special agent spies on Danz and MrSmith is a special agent”.

If we advance the hypothesis that formula $\phi=SpiesOn(MrSmith, Danz)$ in entailed by KB ($KB \vDash \phi$), the Herbrand expansion could be applied to show that $HE(KB \wedge \neg\phi)$ is unsatisfiable.

Comments