Defeasible Logic for Automatic Argumentation

You can’t escape arguments. They represent the fabric of world understanding at any level of resolution you want to interpreter the reality. There is no choice or decision we make without supporting or confuting other choices advanced from others or even from ourselves. Arguments are everywhere.

In a famous old television series, a patient enters a clinic for having an argument but the specialist clear the demand by simply denying whatever patient says. For that, the patient complains that a mere denial of a proposition is not an argument. “An argument - my fellow doctor - is a connected series of propositions that are intended to support or refute some other kind of proposition!”. The client shouts.

Which is not so different from:

“Argumentation is a verbal, social, and rational activity aimed at convincing a reasonable critic of the acceptability of a standpoint by putting forward a constellation of propositions justifying or refuting the proposition expressed in the standpoint1.”

Argumentation is inherently linguistic - in spoken or in written form - and it is a social activity as an interaction within two or more participants with different opinions. Without contested idea, argumentation would not take place. Having an “argument” implies responding to one’s another claim for supporting, attacking or defending positions. Argumentation is mainly a rational activity as an exchange of reasonable arguments, though rhetoric tactics can significantly influence the persuasive power of an arguer.

The nuanced spectrum of rhetoric can hardly be caught by reasoning and logical processes, but they could be resorted by other means. I’m referring in particular to large language models that they can tailor an argument for a particular audience.

Want to read more about it? Take a look into LLMs rhetorical skills

The latter point is crucial for depicting argumentation. Argumentation investigates the communicative aspects of reasoning and can be described as an interplay between logic and rhetoric. While rhetoric is a communication exercise to make an argument more or less appealing to the recipient, logic is a philosophical seek that concern that soundness of a proposition rather than championing persuasion as primary goal.

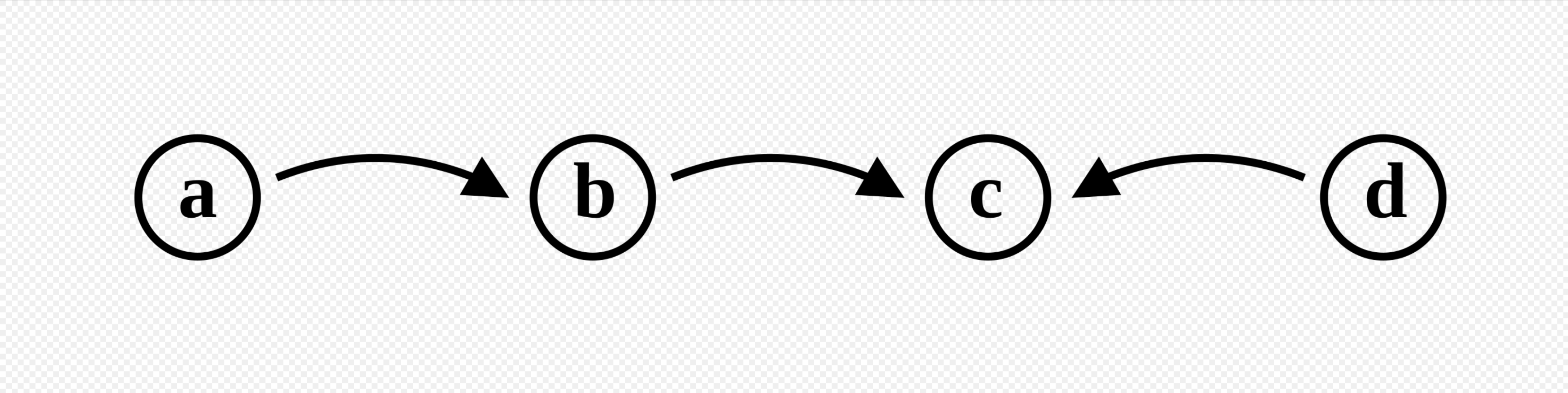

The first introduction to a systematic theory of argumentation comes from Dung and his abstract argumentation framework2, where arguments are nodes in graph. An argumentation system is defined as $S=\langle A,R\rangle$ where $A$ is the argument and $R$ is the attack relation with other arguments. In the example below, $c$ is defeated both by $d$ and $b$. On the other hand, $b$ is defeated by $a$ which neutralizes the attack of $b$ towards $c$. According to the framework, an argument is undefeated if it has no attacks towards it, or if attackers are already all defeated. As the most casual reader might notice, the computational load required to check whether a statement is defeated or not depends on the size of graph, but “Hey man, this is why the computers stand for!”. It’s then beneficial to use automated means to reach a consensus.

structured argumentation

In abstract argumentation every argument is regarded as atomic. Dung’s framework does not dissect arguments into their constituent parts, and that could be seen as an overly simplification. This is why we can turn into structured argumentation. In this way, the different parts that compose an argument are declared explicitly.

An argument is then said to be structured in the sense that normally the premises and claim of the argument are made explicit, and the relationship between the premises and claim is formally defined3.

What are then the constituent parts of an an argument? Toulmin4 has traced a list that could be grossly summarized with:

- Claim. It is an explicit performative at the core of the argument. It’s the conclusion that needs to be proved (claimed) and stated to other participants.

- Data. These are the evidences available that trigger a validation or a refusal of a claim based on some warrants.

- Reason. It could be an explanation with the intent to tell why a claim is true. It could be a justification with the purpose to make a conclusion believable.

- Warrant. It is an implicit assumption that a reason is justifiably true. In the argument “doing regularly sport helps to loose weight” implies that loosing weight (of course, for those overweight) is a good thing. It is the final consequence that a supporting reason or evidence make the claim truly believable.

- Backing. There is plenty of scientific information that confirm low-weighted people can benefit of better health condition much longer than heavy-weight ones.

- Qualifier. Help to bound the claim statement in a scope on which it’s validity can be more successfully validated. Such as “most of the people will benefit”, does not say all in order to not be easily confuted by statistical outcomes.

The approach adopt by Toulmin depart a bit from the usual mathematical form of logic. According to him, the geometrical approach to argumentation is flawed to accommodate the complexity of real-world cases - especially those involving empirical evidence - and fails to capture the context-dependencies of an argument. The list we see above reflects more a jurisprudential4 rather than methematical approach. Real-world argumentation resemble legal cases more closely than math proofs. Most of arguments do not follow scrupulously the analytical syllogism “Socrates is human, all humans are mortal, therefore Socrates is mortal”. Claims are rather supported by evidence, the warrant’s backing, and the possibility of rebuttals.

explanations

Explanations aim to transfer the understanding of how the warrant status of a particular argument was obtained from a given argumentation framework. Walton5 has studied arguments and explanations from a philosophical point of view. He considers that the purpose of an argument is to get the hearer to come to accept something that is doubtful or unsettled, whereas the purpose of an explanation is to get the hearer to understand something that he already accepts as a fact.

Explaining consists in exposing something in such a way that it is understandable for the receiver of the explanation – so that he/she improves his/her knowledge about the object of the explanation – and satisfactory in that it meets the receiver’s expectations6.

practical applications

Argumentation is an art. As an art, argument has techniques and general principles, therefore it is a learned craft. Although there are suggested guidelines and argumentative tools, there is no science of argument. So why automatize it?

As we will see shortly, certain mechanics mostly related to logical reasoning could be intuitively automatized for handling complex issues with multiple perspectives and contrasting viewpoints. I’m referring to applications in the realm of legal systems, take for example how to check the consistency of the immense plethora of laws in a state legal system; or how to automatize intelligent agents to project provisioning orders in a supply chain management.

Courious on how sound arguments might help on explaining given recommendations? Here an implementation where products are suggested based on consumer preferences and grounded knowledge (knowledge graphs) to explain why a suggestion is better than another.

These are some example on how argumentation is permeating through not only our daily life but also the way we conduct business.

Elements of logic

To begin our endeavour in the intricacies of argumentation, we should deep into the mechanics and well-definable aspects of argumentation. We then start with logic reasoning. In here, I arrange the commonalities and peculiarities of 3 approaches to automatic argumentation: ABA7, ASPIC+8 and DeLP9.

negation

One of the most nuanced concept in logic programming is the negation. As we state in a casual conversation such as “the accused is not guilty” ($\neg guilty$) is the form of negation closer to the strict negation one might find in classical logic. The “classical” adjective stands for the kind of logic elaborated by ancient Greeks, with Aristotle as the greatest contributor. According to the excluded middle hypothesis, the accused is either guilty or he’s not. There are no shades of guilt - which are instead embraced by fuzzy logic - only black or white, if you let me indulge in the color metaphor.

There also different concepts related to negation, in particular adopted in practical logical programming languages, which is the negation as failure. According to that interpretation, the negation as failure is a broader concept the reasoning principle of assuming the negation of a statement is true if the system cannot prove the statement itself. What does it means concretely?

When in a supermarket I can’t find biscuits, I can assume that there is no biscuits in that supermarket. I may find them certainly elsewhere, but not there and not in that moment. The negation as failure consider the world-closed assumption: what can’t be found in the knowledge base (supermarket), simply doesn’t exist. This is particularly common in logic languages as DeLP, but might take slightly different names, such as default negation.

defeasible logic

Logic is the basic language of reasoning. Classical logic embrace the law of excluded middle, where what is already known to be true (or false) cannot change due to new incoming information (monotonicity). While those conditions simplify computation and the validation of logic statements, they are limiting the scope on which classical logical might apply:

logical argumentation has the ultimate goal to refuse or support a proposition, therefore the change of truth of any statement is an inherent and desirable property.

Classical logic can’t find a whole place in here. It must be supersede by an elastic framework that contemplate dynamic changes of truth. This where defeasible logic (DL) come to place. In classical style, once a statement is established, it is no longer possible to alter it without falling in conflicts and inconsistencies. Defeasible logic instead, by adhering to the non-monotonic paradigm, embrace beliefs change. Welcoming fresh information, DL may alter previously established conclusions. A way to put it into a practical example could be the statement: “the accused is not guilty if not proved otherwise”. By default, the accused is not guilty unless it is proved the contrary:

\(\begin{eqnarray}\neg guilty(x) &\leftarrow accused(x), not\; guilty(x) \end{eqnarray}\)

With that we make use of default negation which is itself non-monotonic - the $not$ fails when the predicate $guilty(x)$ is activate. Another approach implemented in ASPIC+ and DeLP is the introduction of defeasible rules, according to which a rule normally apply unless a more specific rule overrides the default one: \(\begin{eqnarray}

\label{accused} \neg guilty(x) &\Leftarrow& accused(x)\\

\label{guilty} guilty(x) &\leftarrow& evidence(accused(x))

\end{eqnarray}\)The rule ($\ref{accused}$) affirms that by default the accused is not guilty, unless it is proved the contrary. The following strict rule ($\ref{guilty}$) expresses that if there are evidences against the accused, he is guilty - no matter what could be subsequently determined.

With defeasible rules, there is a distinct separation between the default behavior usually assumed, and the exceptions that might occur. Some examples:

- A bird usually flies ($\ref{defeasible}$), but a penguin does not ($\ref{strict}$).

- In ($\ref{dead}$) a combination of negation as failure and defeasible proposition translated as: “if we’re not sure someone is dead, we can assume he’s alive” - which is why death certificates exist.

The default rule has a specific notation ($\Leftarrow$) that distinguish its fallibility, while the other ($\leftarrow$) denotes a strict rule which has a higher ranking than the fallible one, and supersede all other lower ranking rules. Both rules can coexist in the same program without raising any conflict, but what happens when two or more conflicting defeasible rules apply? DeLP uses a dialectical process to decide which information prevails.

dialectical process

In the sample below, if both $mosquito$ and $dengue$ applies, What is expected the system to assert? \(\begin{eqnarray}

\label{dengue} dangerous &\Leftarrow& mosquito, dengue\\

\label{mosquito} \neg dangerous &\Leftarrow& mosquito

\end{eqnarray}\)If we apply the specificity tactic, the rule ($\ref{dengue}$) should have higher priority because it is more specific. i.e. it entails more literals than ($\ref{mosquito}$).

What if instead, the specificity tactic can’t be applied, because the rules’ specificity is the same?

Some notion of priority must be introduced in conflicting defeasible rules. It could be implemented by defining a series of inequalities representing the relative ranking order:\(\begin{eqnarray} r1&:&walk &\Leftarrow& sunny, free\_time\\ r2&:&\neg walk &\Leftarrow& sunny, allergy\_season\\ \label{pref} r1 &>& r2 \end{eqnarray}\)

In this example, if $sunny$, \(free\_time\) and \(allergy\_season\) apply, it’s definitely better to go for a $walk$ rather than stay home.

An interesting representational device - the presumption - is the defeasible rule with an empty antecedent. As the case of strict/defeasible rules, the presumption introduces fallibility even for facts. Strict facts can’t change, they are infallible like axioms in mathematics. Everything else, such as:

\(\begin{eqnarray}delivered(letter) \Leftarrow \{\}\end{eqnarray}\)

is fallible and can be overturned by a contrasting deduction or a fact \(\begin{eqnarray}\neg delivered(letter) \Leftarrow wrong\_address(letter)\end{eqnarray}\)

compelling arguments

A common definition of argument in the initiatives for automating it, is defined as:

an argument is the minimal set of defeasible rules that allow for the defeasible derivation of a conclusion, ensuring no contradictory literals are derived.

Taking it as a general line of principle of an argumentation system, what should we expect on querying $Q$ in a system? DeLP offers the most granular depiction of how an answer could be. For that, there are 4 possible answer to $Q$:

- $YES$. If $Q$ has no counterargument standing against it, or they are all ultimately defeated. $Q$ is warranted.

- $NO$. If $\neg Q$ is warranted. if the query is “Is the sky blue?” and there exists a warranted argument for “the sky is not blue”.

- $UNDECIDED$. if $Q$ nor $\neg Q$ are warranted. This is a stalemate in the dialectical process. It could arise if there are conflicting arguments of equal strength, leading to a situation where neither side prevails.

- $UNKNOWN$. if $Q$ is not in the knowledge base $K$. In here, the system lacks the necessary information to even begin constructing arguments for or against $Q$. This is the response it would get if $K$ contains information about birds and their flying abilities, and $Q$ is about the price of tea, as this information is simply out of scope.

This nuanced approach to determining the result comes from the system’s handling of potentially incomplete and inconsistent information.

Though the logical argumentation initiatives acknowledge the value of structured and schematic segmentation of arguments, they don’t attempt to capture the Toulmin framework at that granularity level. The simpler structure of an argument is condensed as the tuple $\langle A,L \rangle$ where $A$ is the minimum set of rules (strict and defeasible) and $L$ is the claim. An argument is just a part of the whole system; in DeLP a defeasible logic program is described by $\langle \pi, \Delta \rangle$ where $\pi$ stands for strict rules and facts, on the other hand $\Delta$ indicates defeasible facts and rules. We can say $A$ is an argument for $L$ when:

- Exists a defeasible derivation for $L$ from $\pi$.

- No contradictory literals can be defeasibly derived from $\pi$.

- If a rule in $A$ contains a negation ‘$not\; F$’, then $F$ can’t be in the defeasible derivation of $L$. This condition prevents circular reasoning and ensures that the argument is logically sound.

- It is also promoted the principle of minimality, for which $A$ should only contain the essential set of literals for claiming $L$.

The second point could be explained in the following example. Consider a program $P$ formed by:

\(\pi = \left\{ \begin{array}{l}

night \\

at\_market \\

\neg at\_home \leftarrow at\_market

\end{array} \right\}

\qquad

\Delta = \{at\_home \Leftarrow night\}\)

The same literal \(at\_home\) is strictly negated but also reinstated in $\Delta$ as defeasible rule. This rises a contradiction which this is forbidden in DeLP. If we consider other approaches such as the argumentation systems like GK10 contradictions are removed automatically from $P$ - with an eye on computational costs by performing recursive checks with time limits. We can overcome this kind of contradictions by introducing preferences.

dialectic tree and preferences

The argumentation is the process of deciding the status of all arguments in a program. The verdict whether an argument is valid or not is declared by defeated ($D$) or undefeated ($U$) statuses. Since we tend to avoid binary discrimination, there are also here plenty of flavors of acceptance in arguments. In ASPIC+ are denoted 3 different types of attacks:

- Undercut: An argument undercuts another argument by questioning its premises or assumptions.

- Rebut: An argument rebuts another argument by directly contradicting its conclusion.

- Undermine: An argument undermines another argument by weakening its overall force or persuasiveness, without necessarily contradicting its conclusion directly.

An argument can be directly attacked to its core claim, or indirectly by attacking warrant’s backing. Indirect attack happens when an argument attack a sub-argument (which is a smaller argument, with its own premises, within a larger argument). As previously mentioned for defeasible logic, argumentation suffers from conditions of stalemate among arguments. The Nixon Diamond provides the proverbial example of blocking defeaters. Considering the following argument structure:\(\begin{aligned} \langle A_1, L_1\rangle &=& \langle pacifist(nixon) &\Leftarrow quacker(nixon), pacifist(nixon)\rangle \\ \langle A_2,L_2 \rangle &=& \langle \neg pacifist(nixon) &\Leftarrow republican(nixon), \neg pacifist(nixon)\rangle \end{aligned}\)

The two arguments defeat each other, therefore the answer to $pacifist(nixon)$ will be $UNDECIDED$. Whether an attack from $\langle A_1, L_1 \rangle$ to $\langle A_2, L_2 \rangle$ succeeds as a defeat, may depend on the relative strength of $A_1$ and $A_2$ , i.e. whether $A_2$ is strictly stronger than, or strictly preferred to $A_1$. Where do these preferences come from?

We have already previously ($\ref{pref}$) mentioned preferences in defeasible logic. All that an argumentation system wants is a binary ordering ($\le$) on the set of all arguments that can be constructed11.

The reader may observe that the structure of attacks resembles a tree (or acyclic graph as circular attacks are prohibited). The tree is the dialectic tree where each argument’s element can be defeated by other arguments. A single path within the tree is termed an argumentation line. If a single argumentation line successfully rebuts an argument, the latter is considered defeated and removed.

Giancarlo Frison

-

van Eemeren and Grootendoorst, 2004. ↩

-

Phan Minh Dung, On the acceptability of arguments and its fundamental role in non-monotonic reasoning, logic programming and n-person games, Artificial Intelligence, Volume 77, Issue 2, 1995, Pages 321-357. ↩

-

Besnard, Philippe, et al. “Introduction to structured argumentation.” Argument & Computation 5.1 (2014): 1-4. ↩

-

Toulmin, S. E. (2003). The uses of argument (Updated ed.). Cambridge University Press. ↩ ↩2

-

Walton, D. (2004). A new dialectical theory of explanation. Philosophical Explorations, 7, 71–89. ↩

-

acave, C., & Diez, F.J. (2004). A review of explanation methods for heuristic expert systems. Knowledge Engineering Review, 19, 133–146. ↩

-

Dung, Phan Minh, Robert A. Kowalski, and Francesca Toni. “Assumption-based argumentation.” Argumentation in artificial intelligence (2009): 199-218. ↩

-

Modgil, Sanjay, and Henry Prakken. “The ASPIC+ framework for structured argumentation: a tutorial.” Argument & Computation 5.1 (2014): 31-62. ↩

-

García, Alejandro J., and Guillermo R. Simari. “Defeasible logic programming: An argumentative approach.” Theory and practice of logic programming 4.1-2 (2004): 95-138. ↩

-

Tammet, T., Draheim, D., Järv, P. (2022). GK: Implementing Full First Order Default Logic for Commonsense Reasoning (System Description). In: Blanchette, J., Kovács, L., Pattinson, D. (eds) Automated Reasoning. IJCAR 2022. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 13385. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-10769-6_18. ↩

-

Modgil, Sanjay and Prakken, Henry. ‘The ASPIC + Framework for Structured Argumentation: a Tutorial’. 1 Jan. 2014 : 31 – 62. ↩

Comments