Argumentation in E-Commerce at SEMANTiCS 2022

In a behavioural test in the old seventies, people about to use a copying machine were asked to let another person, the experimenter, to use it first despite there being a line.

“Excuse me, I have 5 pages. May I use the xerox machine?”

Within this request, 60% of the people let the experiment go first. Then experimenters changed the call into:

“Excuse me, I have 5 pages. May I use the xerox machine because I have to make copies?”

The justification is a clear non-sense. It is technically called ‘placebic information’ because, comparably in pharmacy, the given explanation does not contain any justification. You might be surprised that in the latter case the rate of success reaches an astonishing 93%.

This experiment teaches something interesting about how we evaluate the information from the environment. Even without any significance, just the feeling of a reason can change dramatically how we behave. Most of our daily behaviour is accomplished without paying attention to the informative details. This is obviously not new - advertisers know it very well. But we are not doomed to be always fooled, we are conscious when the decisions are more important.

If rather than 5 pages the experimenter asks to copy 20 pages, the results are very different. The more demanding request is evaluated thoroughly and the rate of success does not change between the two cases above. With a placebic reason or no reason at all, the success rate is equally low (20%). Instead, what works is a justification such as:

“Excuse me, I have 20 pages. May I use the xerox machine because I’m in a hurry?”

Admittedly, it is not a strong justification. But some compassionate colleagues let you pass ahead. This justified reason convinced more than double of the subjects, 40%. Is sensibility towards justifications something should be considered with online retail customers?

Argumentation in a nutshell

When we pose an explanation for changing a decision, we are giving an argument that supports or attacks a thesis. Differently from the copying machine experiment, argumentation is a bit more interactive than a single-shot justification. We are, as humans, designed to improve our view of the world through confrontation with others. Stuart Mill once said “Both teachers and learners go to sleep at their post as soon as there is no enemy in the field” to spot the point. We need to be challenged to defend good ideas or abandon the wrong ones. Argumentation involves a confrontation of clashing reasons and sometimes beliefs are inconsistent in the light of new objections, so we must give up some of them.

Argumentation is a fervid research topic and in its basic form, it is simple to explain. I would try here. Arguments can be represented as symbols; they are nodes in a graph of concepts and other arguments. An argument could be in two states: active or defeated. It is defeated when it is attacked by an active argument, while if it is attacked only by defeated ones, it is active. If none of the arguments is attacking, it is still active and can attack others. That’s not really complicated. I show you an example: the argument “Home Office Working” is usually attacked by “Employee Disconnection” argument, which is attacked by “Video Conferencing”. Graphs of arguments grow indefinitely, and within their simple status (active/defeated) they can generate complex dynamics. An activation may cause a cascading effect in a large portion of the network. The main claim can be obliterated by a far away, in the arguments’ graph, single argument.

Argumentation in online retail

Let’s talk about argumentation in eCommerce with a story. John is a professional photographer, and he needs to learn about an advanced camera. After adding to the cart an online course, the system detects a high risk of churning. John most probably won’t take that course, why? It’s difficult to guess, but we make suppositions by properly using the knowledge system which expands the catalogue products with a wider semantic network. A knowledge graph of concepts that the system can exploit for making sense of what’s going on with John and his reluctance to finalise the checkout.

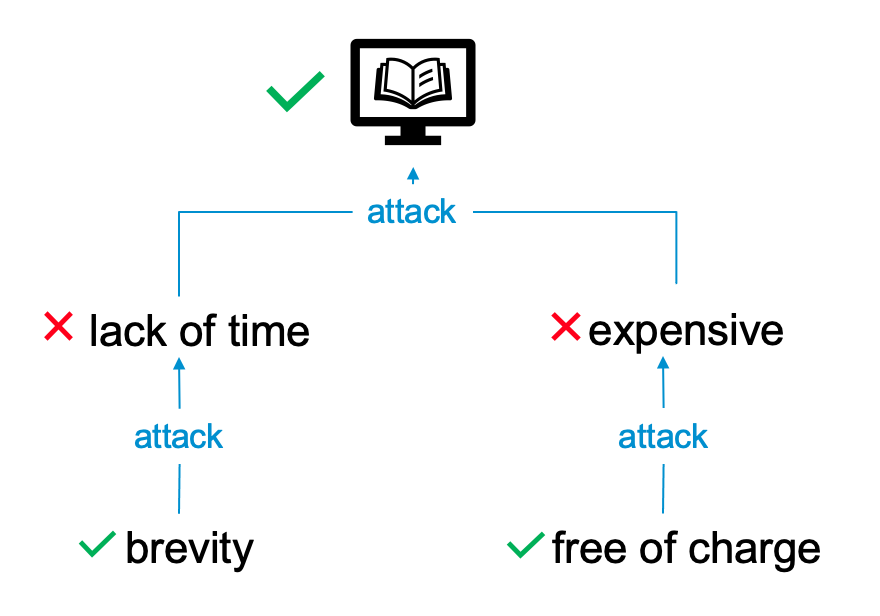

According to the knowledge base, a learning course requires time, which might be an issue for a busy professionist. How does the system know whether this is the case? Semantic algebra is very helpful on that. But it is just an hypothesis among many others, the system needs validation. Suppose John confirms, we know he does not have time for it. The course is just 20mins long (a crash course indeed), that compared with others of its category is short. This is a counterargument that invalidates John’s misconception.

John is convinced about that, but there is another problem, his budget is very tight. But wait, this course is free of charge, therefore the ‘low budget’ argument is defeated, and the main claim (John attends the recommended online course) is active and valid.

I don’t know whether John has enrolled in that course, but the system attempted to change his mind. His misbeliefs have been neutralised by reasons the system has been able to scrutinise from the knowledge system.

We were also lucky, the arguments provided do not attack each other by forming loops in the graph. That would considerably complicate the argumentation. I give an example of what could happen. Think of three football teams, Italy, Germany and Brazil. Let’s assume Italy wins against Germany (not always btw), Germany beats Brazil, Brazil beats Italy. In the knockout stage, who will be the winner? Well, it depends on how the competition is set up. It is the Argumentation System that has to set up the proper strategy for achieving the desired goal. There are other cases where things get complicated. Let’s assume not all arguments are equally important and arguments are not true (or false) with the same intensity.

Comments