Bayesian Networks. Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love Probability

The tragedy happened to the AirFrance 447 more than 10 years ago, in 2009. The flight took off in Rio de Janeiro and was planned to land in Paris. But it never arrived. It suddenly disappeared in the middle of the Atlantic ocean without any warning. Immediately, rescuers reached the zone and what they found were just some wreckage and corpse. All 228 people onboard died in the crash. As in any flight incident, the priority was on recovering the flight and voice recorder. The devices emit acoustic beeps when they get in contact with water, so the first mission scanned with passive sonars portion of the area where presumably the black boxes were laying. The second mission instead, scanned the ocean floor with active sonars. US Navy and underwater vehicles searched for it, but after 3 years of research there was no sight of wreckage. Then, an agency was appointed to find the boxes, but this time with a different strategy. They scrutinized all possible information that might contribute to having a clue on the position. They accounted for data about flights’ trajectory on past crashes, wind and water streams, distributions of wrecks and bodies on the surface. All elements that can help to predict where the wrecks of the unfortunate flight were laying down were considered and weighted. The new system designed with those elements traced a map with the probability to find the recorders. In less than a week, in just 5 days of research, the wreckage was located and eventually the boxes recovered. What did they apply was Bayesian inference.

Bayesian Inference

Bayesian inference is just about updating our belief according to evidence collected in the environment. It is an elegant and practicable pattern a software program can encode and transfer in running applications and very intuitively, this is how we make decisions in our daily life.

Right now, I look out of the window and I see a plumbed sky on the verge of an imminent snow. I’d say by the available evidence that chances of snow this afternoon might peak at 50%, \(P(⛄)=\frac{1}{2}\). Maybe things turn the forecast into a slightly sunny day, but according to what I see, this is unlikely. I simply adapt my idea of weather to the circumstances of the case.

Let’s assume there is a thermometer outside. I can read the temperature and it is far from the optimal one for snowing. Accordingly, my belief about a white landscape this afternoon drop down considerably. What I know is that temperature influences the snowing event, or in other words, snowing is conditional to the low-temperature event.

\[P(wish\; to\; know \mid known)\]Conditional probability relates what we wish to know to what we already know. It is a simple mathematical morphism from an entity - the low-temperature variable, \(P(🥶)\) - to another, in this case the snowing event \(P(⛄)\), the one we want to estimate.

I want you on this other example. You know the size of this billiard wherein I throw \(N\) balls. I want you to tell me how many balls go into the black square. I see you already gaudy with the formula in a silver plate ready for me: \(P(N_{square}) = \frac{Area_{billiard}}{Area_{square}} N\)

What if I pose a slightly different problem? What I wish to know from you is the area of the entire billiard given that the balls are already countable in the black square. Now your expression is a bit gloomy.

In the first case we map the forward probability from areas to \(P(N_{square} \mid Area)\), in the second the inverse probability \(P(Area \mid P_{square})\).

You intimately convey with me that they are two faces of the same coin, and even more, the inverse probability sounds like the forward probability from a different perspective.

While our judgment is more reliable in one direction - when it comes to map from cause to effect - it is certainly less accountable in the opposite direction, from effect to cause. Estimating the number of balls falling into the black square (effect) is easy when we know the areas (causes), it is less intuitive when the problem is upside-down.

I think the way we encode causality is shaped along our evolution. In the jungle the reaction to dangers of our ancestors must have been quick and reliable. Deducing the cause from an effect is a higher cognitive skill that unequivocally distinguishes sapiens and requires a little more mental effort than the reactive skill.

If you allow me for a moment the pill of speculation, I’d say that you can see analogy with NP problems, the class of algorithms whereby it’s easy to verify the solution, but the solution is arduous to calculate. It’s easy to verify that two numbers are the factors of a third number, while it is quite laborious to find them from their product.

Back to Bayes, he’s still remembered after 250 years for one important thing. He formulated the famous Bayes Rule which describes the passage from forward conditional probability to its opposite direction, the inverse probability. He helped us to codify our assumptions from one direction, where we are more confident, to the other in mathematical - aka programmatically - manner.

I’m still in front of the window, but in this scenario I don’t know anything about the temperature. I’d want to have moved away the thermometer so I would not know how cold it is right now. I would imagine a silent snow and watch the roofs slowly turn to white, like in a classical winter film. Let’s assume that is all real. I wish to know how cold it is outside, given that it’s snowing.

For that, I use the Bayes Rule for deducing the inverse conditional probability \(P(🥶 \mid ⛄)\) from the previously mapped \(P(⛄ \mid 🥶)\).

I want to point a couple of considerations on this formula. The first regards the impact of this rule to our knowledge after the event of snow. The formula indicates that our belief after that event is no lower than before we assisted that event. The posterior (the left side of the equation) will be never lower than the numerator in the right side. That means our idea of low-temperature will come out stronger than before.

Our belief will be even stronger as much as the probability of snow is low, and that’s the second consideration. \

Rareness is highlighted also in information theory, by which the quantity of information is higher in rare events than in common ones. \

Think for a moment about the Sahara desert, you imagine it hot and sunny, always. If you find snow in south Libya, you’ll be frankly surprised. The Bayes rule doesn’t contradict this principle and emphasize rareness rather than commonality.

If you want to know more about Bayes Rule, there are a couple of examples - actually a couple of counterintuitive puzzles - that might be a good insight on Bayesian mechanics.

Bayesian Networks

If you are a supporter of composability in software development, you would enjoy that random variables form graphs of edges connected by chains of conditional probabilities. Probability graphs are bayesian networks aimed to aggregate information at scale for making decisions.

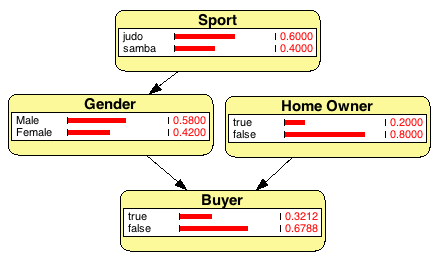

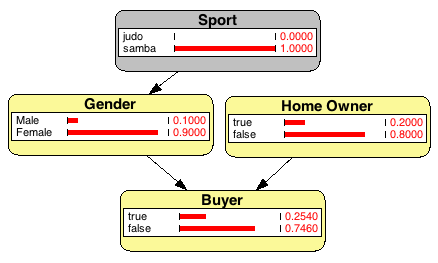

Let’s assume you’re running a successful web store and you collected a fairly amount of information of the characteristics of your customers - sales and marketing analytics. This is your prior knowledge.

When a new user visits your store you know merely nothing about him/her. The user interacts on the website and some useful information might be indicative of the profile. For example, we can estimate the user is actually a woman because she dances Samba. The chain of inferences doesn’t stop here, and we know that our prior estimates the probability she’s going to buy our product is lower of a male. Similarly, we can estimate an increase of chances to sell her whether we know something about her status, in particular whether she’s the owner of real estates. Something similar to the search of the AF447 wreckage, but for completely different purposes.

Dynamic Bayesian Networks

If we extend the concept of network of beliefs in a time sequenced process we get the abstract of what is named Dynamic Bayesian Network. It is a Bayesian network with a feedback loop, whereby the output of an interaction feeds the input of the subsequent step. If you are familiar with recurrent neural networks, it’s not a giant leap to identify the similar pattern with DBNs. The possibilities - and the complexity - grows exponentially by introducing this architecture. In the following example, the weather affects the humidity of the air, which (hypothetically) has an influence on the weather of the next day. The network keeps a state of past interactions, in particular might take in account what was an input several steps ago.

This is a brief introduction on Bayesian networks with categorical variables, the easiest type of random variables to begin with.

To conclude, the causes of the incident AF447, are a bit scary. A technical failure that should be managed without risks, has been handled with unbelievable negligence by the crew that committed a series of mistakes, ultimately ending in the crash. RIP.

Comments