What is Understanding? Principles of Comprehension for Computer Programs

Imagine that you receive an email that contains only symbols you have never seen before, and you are provided with instructions on how to relate those strange symbols. The instructions are in plain english and your task is to apply the instructions to the given symbols and reply back unknown scribbles, the results of the transformation. We can define the documents: the incoming email is a set of questions, while the instructions are the program, and what you send back are the answers. For complicating the task, you are demanded to complete the following. You receive another email in english (or on your mother tongue): “A client enters a restaurant and orders a steak, but after being served he quits the restaurant, angry for the burned steak, without paying”. You are requested to answer to the following question: “Did the client eat the steak?”.

In the first task you are so practiced and the programmers so smart that your answers sound very natural and intelligent to the receiver. Although you don’t know, the strange symbols are nothing but ideograms of a dialect present in a remote region in China and they’re carrying the same meaning of the second script, which is in english and you understand perfectly. The receiver is astonished by your answers and he firmly believes you speak his local language as well as english, despite you have merely executed the given instructions without understanding anything of what you wrote in Chinese.

This is a variation on the “Chinese room” theme (Searle 1980), a well-known argument against the famous “imitation game” of Alan Turing, also known as Turing’s test. Likewise in the mentioned task, the Turing’s test is passed by convincing auditors that the questions are genuinely answered by a human being. The Chinese tester voted for granting you the mastery of Chinese, but you acted exactly like a computer, by executing some given instructions and ultimately, without any clue of what that actually means.

Searle wanted to point out that the process of understanding is a crucial prerequisite for being considered an intelligent being, rather than an irrelevant detail as depicted in the Turing’s test.

Even though the Searle’s argument appears intuitively irrefutable, I investigate what actually “understanding” is and how it can be reduced and decomposed into small units and what is necessary to get such ability. I want to convey you with me into an understanding of the understanding process.

Learn for understanding

The term understanding is used in many different circumstances. It is a general term and may refer to:

- Understand a function. (e.g. How to use the coffee machine).

- Understand a person.

- Understand a concept.

- Understanding as problem solving.

- Understand a motion. (e.g. Dancing).

- Understand causality.

Those usages appear to have distinctive meanings but I would rather structure the significances of the term into two main branches: the enacted and the reflexive understanding. One of the classic examples everybody mentions about an ability that once acquired will be never forgotten, is how to ride a bike. The ability is assimilated throughout experience and activity, and after being shaped by countless grazed knees in childhood, cycling goes smoothly without conscious intervention. This is an example of enacted performance which inevitably comes after the reflexive understanding, the conscious, intensive, effortful mental process.

Understanding a language is also an enacted and routined activity, unless it is referring to the precise task of learning a language. Even though you’ll never forget your mother tongue and it seems to be an innate talent, it took many years of practice and mistakes to get fluent in your own language. When you listen and understand a sentence you are accessing and matching cognitive structures in which you can place the sounds emitted by your interlocutor. Very different sensation compared to when someone talks to me in German assuming I’m fluent in it, while I barely understand just parts of the discourse. In that precise moment not all what the speaker says fits my representation of that language, and bigger the discrepancy, less fluent I am. The awareness of unfitting is the ringing bell of my lack of understanding, and I should invest more time on fitting the gaps throughout reflexive understanding, the exercise that helps to cope on novel experiences.

Understand a circle

The word “to understand” has the synonym “to grasp” and it is something very similar to how understanding is depicted in daily conversations with the say “got it” and “catching on” and recalls the idea of perception.

Just for a moment, close your eyes and imagine to hold a tennis ball in your hand and try to focus on it. You should figure the feeling of the woolly surface trailed by grooves, and as you fiddle it with your fingers, you feel the rounding of the object. You associate the touching sensation with the visual depiction of the roundness, a sphere. The idea of a ball is not a static multi-sensorial representation, it is a manipulative skill you have that lets you to think about this object as capable of rolling and bouncing, for example. You might also collocate the roundness property into a usable affordance, and if you need to move a heavy weight along the corridor, you will probably choose a pulley, because wheels can roll over the ground.

The understanding of “circle” rests on the model that enables it to do “circling” with your mind and allows you to formulate abstract theories not immediately attributable to the senses. The definition says that a circle consists of points equidistant from a fixed point. That’s the result of a deeper level of reflection, the one that can introduce new unforeseeable connections between unrelated elements.

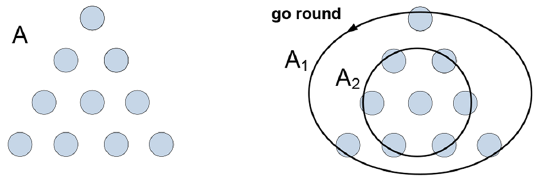

When fishes are trained to recognize circles, they connect the shape with the contextual significance (feeding) but they don’t make sense of them. To appreciate the distinction between a mere knowledge (circle => food) and understanding, I present the problem above as an example of manipulative skill where the observer is going to attribute the “circling” property to the figure in order to solve it. What is requested is to invert the figure A with the minimal amount of moves. In the right I present a schema that facilitates comprehension. Group A1 is not recognizable as a circle in the original figure A, likewise group A2 doesn’t look like a point, but if you imagine it like that, then a solution appears more attainable. The mental action of grouping the dots is imputed - not recognized - when it comes to perform the “go round” task, the task that allows to invert A. Understanding requires representations and operations that enable one to create or manipulate concepts or, like in this case, circles. The model should account for manipulating a tennis ball, follow a circle path, performing circular movements, hold the object in the hand with closed eyes and visualize it. Expecting (not be surprised of) the circular edge, for example of a coin. It requires to actively engage with the cause of sensations.

Understanding the sewing machine

One of the myths that as a student one should abandon is the legend of the gifted scholar who understands all in the first shot. While adepts of this belief affirm that one can either get the concept or not, and if it doesn’t come, it won’t ever come. Another group - the incremental learners - hold on the idea that learning for understanding requires time, practice, effort and refinement.

The process creates (or destroys) cognitive paths between concepts, and it takes energy. We want to feel the “aha” sensation, and we feel that way to the extent that we can believe that what we have just seen is like something we have already previously seen. Conversely, when we don’t find a correspondence we begin a process of adaptation of old theories (old understandings) to new areas. Is it associated with creativity? If it comes to finding an old pattern, determine to what extent differs from the current situation and begin to adapt it, yes it is. Broader the toolset of your cognitive skills, more creative and fantasious the new associations might look like.

This is particularly evident in the sewing machine experiment.

Volunteers were asked to understand a complex physical device, a sewing machine. Everybody knows what it is used for, not all of us are aware of the underlying mechanisms (for a even more common device that very few know how it works, get a glance into your flush toilet at home). The process is iterative and when they claim to get an idea about the machine, they are at the just the beginning of a deeper level of comphehension, on which they realize that what they have understood so far is incomplete, and further inquiries are needed.

Understanding is an imperscrutabile subjective experience for which we have very limited tools of investigation. Two of them are explainability and problem solving. The former is the justification posed by the understander on why something is the case or not, the latter is the activity that denotes an intelligent behaviour as result of understanding. In this experiment the scientists turned the invisible explanation process into a visible one. The participants were encouraged to work together in pairs into a “constructive collaboration” by talking to each other and by using pencils, paper or extraneous material to mimic the threads.

The sewing machine represents the prototype of hierarchical mechanisms with 3 main levels of understanding.

- Level 0 is the fundamental function of the machine: to make stitches.

- Level 1 is the looping-over the two threads, the upper and the bottom one, though for some purposes the explanation of this level would be satisfactory it introduces a topological puzzle that can be solved on level 2.

- The last level is the more tricky to get how the machine works. Hereby, the volunteer should grasp how the threads are tied together; the lower thread is wounded in the bobbin which serves as free end.

There are other levels but I assume at this point the flow is clear: for catching the mechanism of level n, one has to get how it works at previous level, the level n-1.

This experiment shows that the process follows the functional hierarchy and it is soaked with conflicting phases. People might initially identify the functionality, then they confute it, then they search for alternative solutions, then propose the explanation. They criticize again until they confirm the achieved understanding. When a mechanism is confirmed, they follow to the subsequent level until they reach full (acceptable) understanding of the machine. Roughly when one finds an explanation it is felt as understood, when the function is questioned or criticized and one starts to search for its mechanisms, this gives a sensation of not-understanding.

The repetition of searching, questioning and searching again recalls the role of counterfactual simulation by posing the what-if-things-are-different interrogative for searching appropriate theories of the machine.

Another fundamental element caught by the experiment is that the criticizing phase is an active and fundamental task. It has been confirmed that participants with less understanding are the most critical on the identified theories. That could be due to different directions in which participants are focusing their attention. It is similar that one may understand how Michelangelo built the David, without understanding why it is beautiful.

The explanation of personal point of view and the confutation with other theories drive to change continuously the mental map of meanings, and this model runs by searching for explanations and confutations till it settles to an understanding.

Explanatory theory of Understanding

The sewing machine experiment emphasizes the role of explanation. The participants joined the experiment with very different backgrounds, and different knowledge leads to different insights. Given that most people fail to understand each other it seems not a big loss to admit what facilitates perspicacity is a high degree of affinity. If we think of understanding in terms of spectrum, It culminates in “full empathy” when affiliation is high in the case of old friends, brothers or other such combinations of close relationships. It falls into a minimal level of comprehension described just as “make sense” on which events are interpreted in terms of coherent although very incomplete picture. The relative closeness in experiences are reflected also in the similarity of mental models that justify our actions, and if we can explain what and how our close friends are doing we can understand them better too.

The explanation (and the failure of explanation) is itself an active element stored in our memory, and it is reused when similar circumstances show up again.

If understanding an idea means that the agent should be able to explain why it is the case, the agent should be able to explain, to some degree, the concepts that are related to it, like in the levels (0,1..) of the previous example. By using this approach, we should go deep indefinitely into the hierarchy of understandings. In the example of the tennis ball, one should have a grasp of what tennis is and why people do sports, but also what could be the material of the ball and so on into an incredibly deep graph of meanings. To which degree a plausible understanding should penetrate the hierarchy of meanings?

Mathematical axioms represent the premise and the foundation of any following theory, and they are not demonstrated to be true because they already are true, without any further justification. The Goldbach conjecture states that any even number greater than 2 is a sum of two prime numbers. Even though it is not proved, it is verified up to 4 * 10^18 and I guess that it is widely taken for granted. Likewise, the irreducible unit of understanding can’t be explained and we can assume that with a finite degree of explanations, the concept under scrutiny could be considered understood. At the end of chain of reasoning an hypothetical computer program would respond: I did that because you asked me to. Sound acceptable as the ultimate answer?

Computational understanding

Explanation is not a mere addictive beside the main process of understanding, it is itself a choreographer and runs restlessly looking for affirmations, confutations and alternatives. But can anything be used as material to justify an affirmation? If I take a random sequence of numbers for example, the only capable theory I can use to relate them is just… the sequence itself. Would we still believe we understand them? The theory has to be simpler than the data it describes otherwise it doesn’t explain anything. If the law that describes the data is an extremely complicated one, the data is lawless. The Occam’s razor describes perfectly the concept for which the simplest explanation is the most likely the right one. The smallest program that calculates the observations is in fact the best theory a system can generate as a result of its understanding. This is where the say “Comprehension is compression” fits perfectly into the discourse.

In this article I mentioned multiple times the essence of mental models, some kind of memory structure that the agent should be able to manipulate in elastic performances and interrogate it. The model should be “runnable” because nothing will be got from it without running it. An agent when facing a new experience is using the memory in two distinct ways, the bottom-up and the top-down approach. In the bottom-up the information from the real world are matched with past memories, in the attempt to collocate the current event in the universe of known experiences (allegories). After the bottom-up revival of the high-level meaning, this activation would trigger a top-down inquiry of the various possible relation with other entities in the database, for eliciting the most salient possibilities. If it finds new information confirmatory, the initial hypothesis will be maintained and further elaborated; otherwise it disconfirms the assumption and constructs another one, ultimately consistent with the input data. Agents should go beyond the specifics of what the input actually tells them. Their interpretations should include material completely unaddressed by the input data.

Eventually, the problem facing an automatic comprehender is analogous to the dilemma a detective faces when trying to solve a crime.

Will we be able to create an automatic Sherlock Holmes?

Bibliography

- Understanding understanding. David Rumelhart

- What is Understanding? David Perkins

- Constructive Interaction and the Iterative Process of Understanding. Naomi Myake

- Explanation Patterns. Roger C. Schank

- What is understanding? An overview of recent debates in epistemology and philosophy of science. C. Baumberg

- The Limits of Reason. Gregory Chaitin

Comments