The Meeting of Minds

“I’ve broken it off.”

“What do you mean, you’ve broken it off? She was the best thing that ever happened to you. I loved her too, if the truth be known. You’re such an idiot! I have a mind to…”

“I mean I’ve broken the tip off my pen.”

“…Oh.”1

Although we can easily identify when a conversation veers off course, we are often unaware of the inner workings of our mind that silently orchestrates the communication process. This post marks the inception of a brief series, aiming to illuminate these mechanisms through a distilled interpretation of Professor Gärdenfors’ “Geometry of Meaning.” This compelling collection of theories offers valuable insights into the nature of semantics and how our cognitive faculties process it. Exploring these subjects has sparked my curiosity and fascination, particularly in relation to the ultimate objective of developing automated systems capable of emulating our cognitive processes to solve problems on our behalf.

Layers of Knowledge

What is that knowledge and where does it come from? Knowledge stands for a set of justified believes, a core of interconnected ideas such that the causal relations among them give us a resemblance of truth. Information can help us to get knowledge but it is not the mere data - aka Big Data - sufficient to associate the mental affordances we need to function in the complex world. As affordance I intend the possibility of an action an entity can offer. We are continuously encountering strange situations that we have to figure out which support from the toolset of knowledge we should pick up for deciding on what to do next.

What we think, what we plan to do today or in the distant future is corroborated by what we know. We are the climbers of the ever growing mountin range of grasp we started to absorb even before we born. We are surfing the deep pack of knowledge we gathered about ourselves and the world.

The metaphor of the mountin as the knowledge, and the climber as the agent that seeks for new mastery, suggest us that agents are positioned at different altitudes - different granularity of knowledge - and then collected background, might be different. In the short dialog I used to open this post, Bob and Alice align themselves into a shared knowledge, but sometimes it is far from simple to establish apparently simple truths. Bob is ambiguous in his ‘I’ve broken off’; he does not specify what he has actually broken off with, and Alice, the interlocutor, wrongly infers he’s leaving his girlfriend. To create the basis of reciprocal understanding Bob pulls the communication level down and he raises Alice’s knowledge by precising that what is broken is the tip of his pen, and not his relationship.

I guess everybody agrees on the importance of sharing a common background of knowledge and Bob shows us we shift from a high semantic layer to a lower one to meet our interlocutor and restart the coordination from there. This admits that knowledge lies in hierarchical structures where the first rung of the ladder is populated with the fundamental and cognitively irreducible terms; they form new and more abstract concepts with increasing abstraction as long as we climb the ladder, in the upper layers. Simon Winter explain this idea of layered levels of knowledge analyzing how a mastercraft teaches a novice on how to replace a violin’s strings, where non-verbal communication is also part the game. He summarizes context levels into:

- Level 3. Non verbal communication. People interact with minimal information exchange.

- Level 2. Instruction. coordination of action is achieved by instruction.

- Level 1. Coordination of the inner world. people inform each other so as to reach a richer or better coordination. It can also be achieved via questions.

- Level 0. Meaning of words. Lowest level people negotiate the meanings of words and other basic communicative elements.

I don’t know whether there is a finite number of layers or it is open-ended, but on a high level of shared knowledge, the communication style would flow according to the ‘the obvious goes without saying’, where the implicit understandings are at their maximum. I’m also a bit skeptical of the lower bound of this ranking. If we take as granted that meaning of words can be decomposed into a finite set of conditions that are necessary and sufficient to describe the meaning, it is clashing with the level 0 where concepts are irreducible. If I open a vocabulary and every word - even the simplest one - is defined by means of other words, the case of circular loops in meaning references is inevitable, and inequivocal sign of inconsistency.

Communication as Coordination

Language and other forms of communication open the way to various types of engagement. Sophisticated collaborations can enable collective creation of value that can’t be done by single individuals; they’re fruits of communication. If we can summarise in a single word what communication stands for, I would recommend coordination. Coordination among interlocutors is a practical way to point at objects, places or actions, but also as alignment of intents, ideas, persuasions and even entertainments. More generically, coordination is a convergence of mental representations.

If coordination implies a transfer of information, it is expressed in several forms where language is the most rich and expressive one. In the dawn of humanity when the communicative acts became more varied and detached from the immediate and practical purposes, the value of meanings, or semantics, turned out to be more salient in communication. The coordination among participants is an iterative process where the meeting of minds ultimately converge in an alignment of meanings. Sounds almost romantic! As borrowed from maths, the metaphorical meeting point is also named fixpoint. A fixpoint is a value for which a function returns exactly the same value. It is a value with which a specific function works as an identity function. Let’s unfold how the process occurs in our dialog.

- Before Bob speeches out with Alice we can assume he has his own imperscrutable beliefs that we can’t have access but he’s willing to express to his friend.

- Bob pulls out of his linguistic toolset for transforming his ideas into verbal sentences.

- Once Bob has expressed his view, Alice can transform such sentences into her inner mental representation.

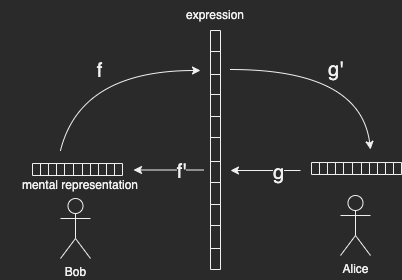

More mechanically, Bob applies the expressive function f to his mental idea and the sentence is passed to Alice, then she applies g’ - the interpretative function - and acquires the meaning of that sentence, which is returned back to Bob as she has understood. Alice encodes her understanding into expression, then Bob applies f’- the inverse function (cofunctor) of f - to acquire Alice’s expression. If the idea generated in the round back coincides with the original one, the coordination has been successful. If the original and derived ideas don’t overlap, the alignment failed and Bob will attempt to correct Alice.

For it to be effective on how to fix Alice’s misunderstanding, the distance between Bob’s idea and what he derived from Alice’s feedback should be articulated enough to convey a rich sort of information. It should not just give a quantitative distance from the successful fixpoint, and also a qualitative account on how they differ from each other. This is why the discrepancy should be encoded as a vector in order to be also descriptive of the conversation’s status. This introduces the next topic of conceptual spaces, which poses the representation of semantic values in the between of symbolic AI and neural networks.

Continue the reading with conceptual space as neurosymbolic representation

-

http://fiftywordstories.com/2013/09/11/connell-wayne-regner-oh/ ↩

Comments