Justify Recommendations with Semantic Technologies

E-Stores loose sells due to the negative biases of consumers. While salespeople give proper reasons to change consumers misbelieves, it is problematic to address those issues in an online shop. I have proposed a method to combine semantic graphs with logic programming and symbolic machine learning to restore consumer’s confidence. The digital agent detects what are the problems users might have and offers them explanations and valid arguments for not worry about, or why a given recommendation is more suitable than others.

👉 hereby, a brief informal account of the idea behing this patent.

The copy machine experiment

In a behavioural test in the old seventies, people about to use a copying machine were asked to let another person, the experimenter, to use it first despite there being a line.

“Excuse me, I have 5 pages. May I use the xerox machine?”. Within this request, 60% of the people let the experiment go first. Then experimenters changed the call into:

“Excuse me, I have 5 pages. May I use the xerox machine because I have to make copies?” The justification is a clear non-sense. It is technically called ‘placebic information’ because, comparably in pharmacy, the given explanation does not contain any additional information. You might be surprised that in the latter case the rate of success reaches an astonishing 93%.

This experiment teaches something interesting about how we evaluate the information from the environment. Even without any significance, just the feeling of a reason can change dramatically how we behave. Most of our daily behaviour is accomplished without paying attention to the informative details. This is obviously not new – advertisers know it very well. But we are not doomed to be always fooled, we are conscious when the decisions are more important.

Argumentation

Differently from the copying machine experiment, argumentation is a bit more interactive than a single-shot justification. We are, as humans, designed to improve our view of the world through confrontation with others. We need to be challenged to defend good ideas or abandon the wrong ones. Argumentation involves a confrontation of clashing reasons and sometimes beliefs are inconsistent in the light of new objections, so we must give up some of them.

John Stuart Mill once said “Both teachers and learners go to sleep at their post as soon as there is no enemy in the field” to spot the point of argumentation.

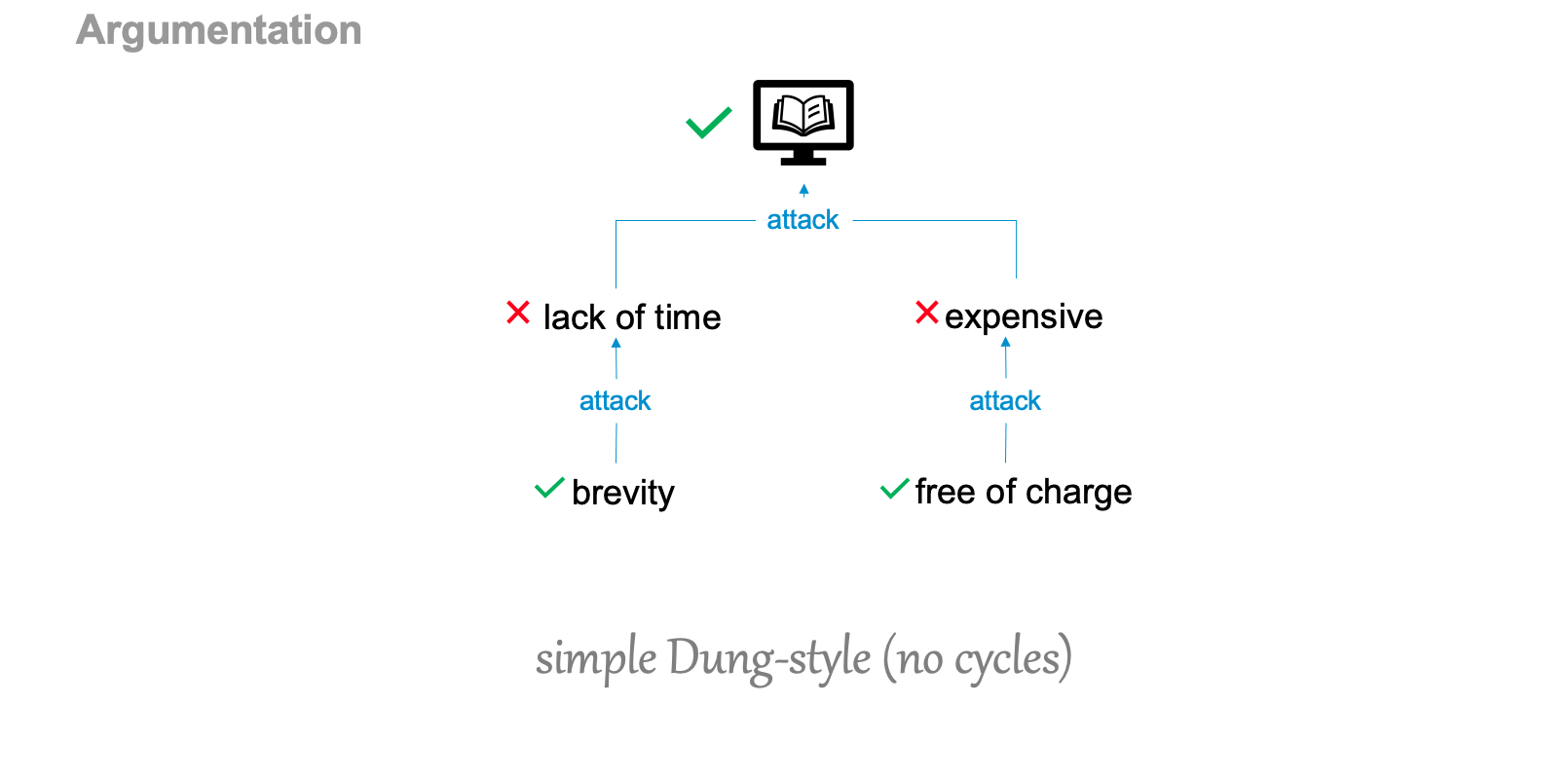

Argumentation is a fervid research topic and in its basic form, it is simple to explain. I would try here. Arguments can be represented as symbols; they are nodes in a graph of concepts and other arguments. An argument could be in two states: active or defeated. It is defeated when it is attacked by an active argument, while if it is attacked only by defeated ones, it is active. If none of the arguments is attacking, it is still active and can attack others. That’s not really complicated.

The argumenting e-commerce

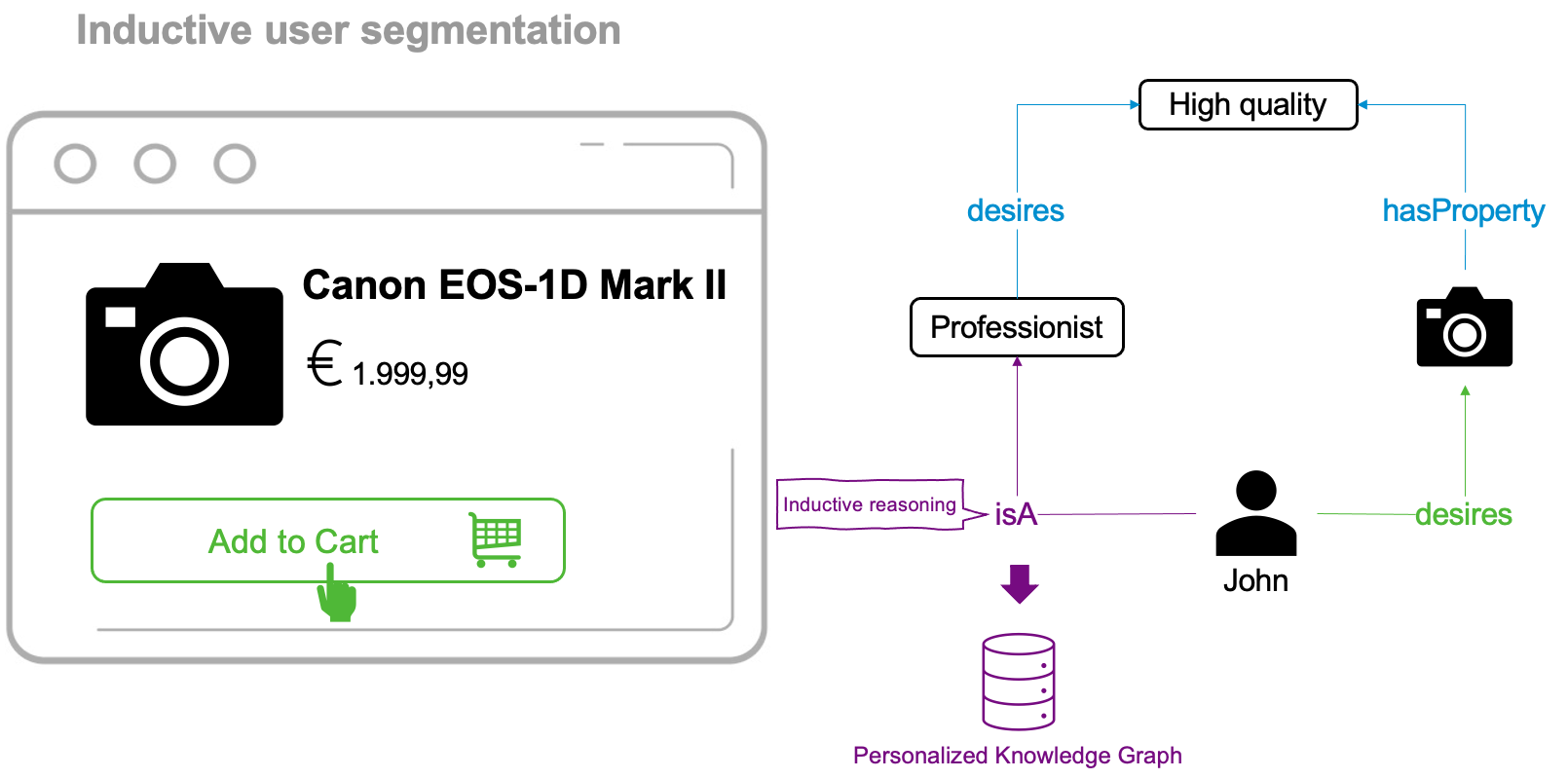

The eStore sell photography items, and any product is represented as concept graph and the system knows some property of articles for sales. We know that the Canon EOS-1D is a high quality one and professionists desire high quality cameras. John, the user browsing the eStore, after a careful inspection decides to add it to the cart. It could be interpreted that John desires that product and we can store this information in his personal knowledge graph. This information is used for enabling further reasoning about who John is, and what are his peculiarities. We can infer that maybe John is a professionist. Why? Because John and professionists share common desires. Is it enough to be certain of that? Of course not. But it is a hypothesis that the system should consider.

Churning Alert!

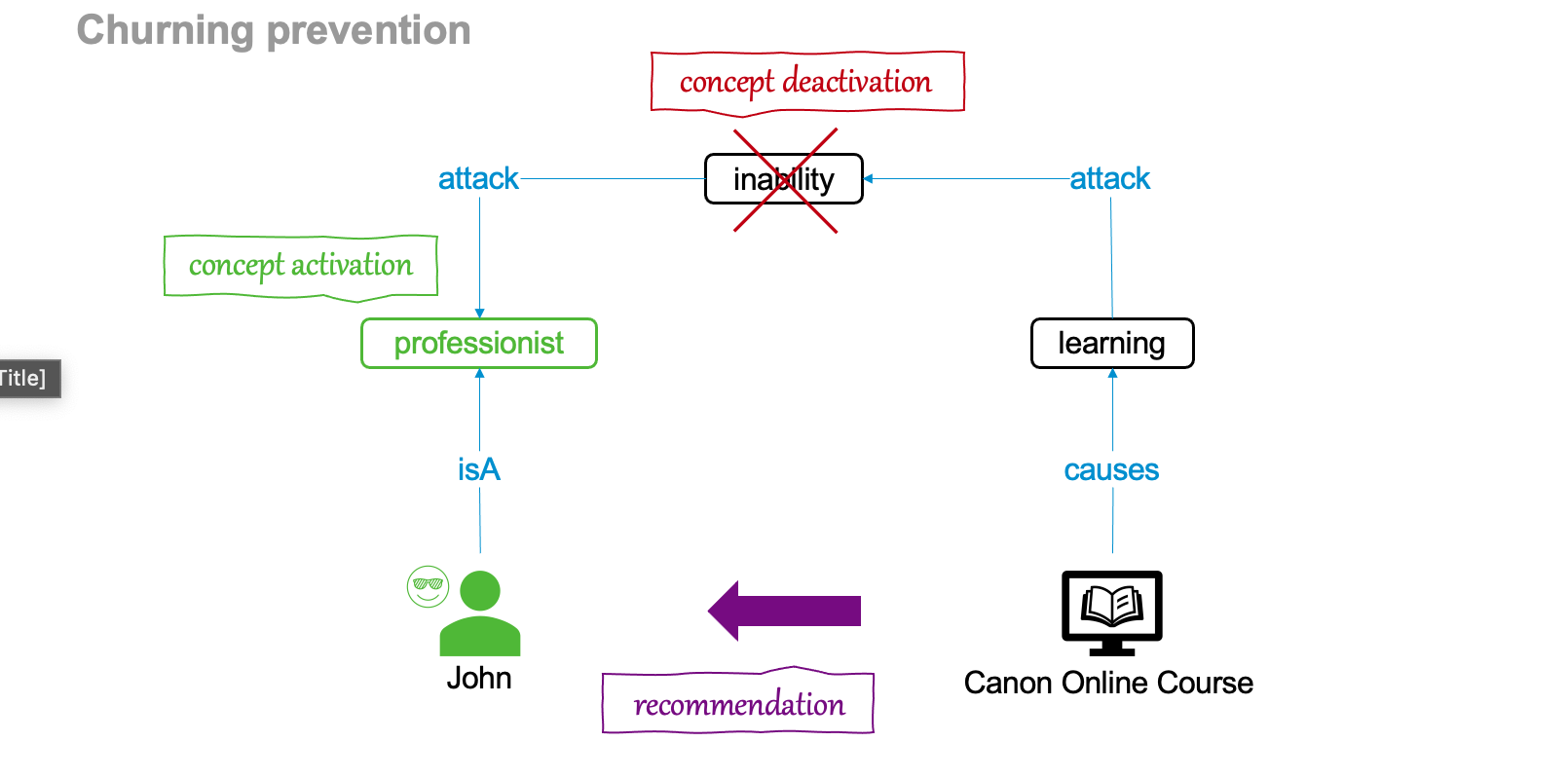

But there is a problem. The eStore’s machine learning system is prompting some alarms on John. We know that the chances John will finalize the purchase are low (for a variety of reasons) and the system has to do something about that.

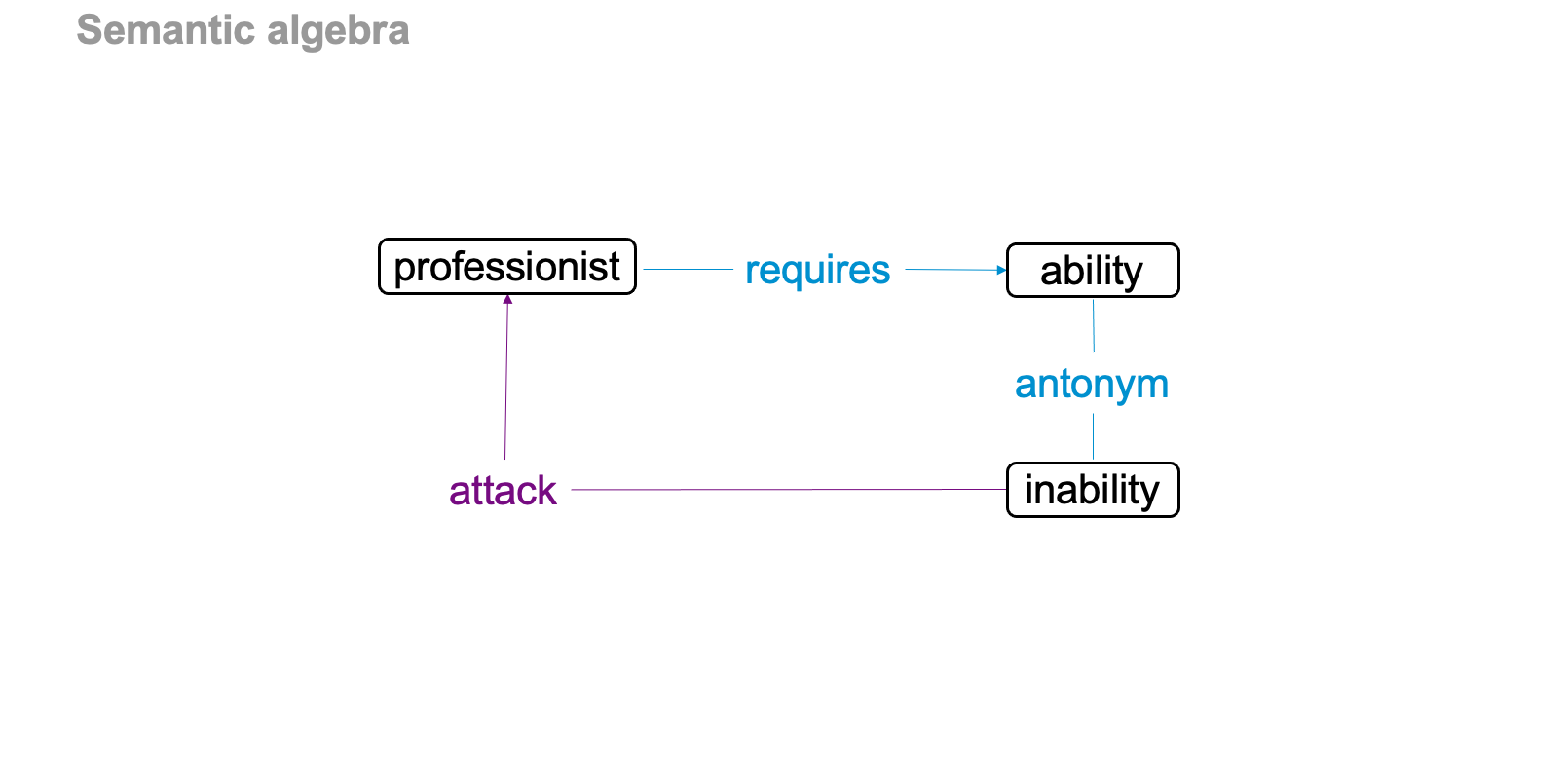

I introduce now some logic primitives that lay the foundation of logical argumentation. We know, as it is encoded in our knowledge base, the a professionist requires some kind of ability to perform his job, right? Ability is a concept, and its antonym is inability. We can infer that inability prevents anybody to be a professionist. So the inability’s argument is attacking the professionist’s one. Here we see a pattern, specifically (sorry for the logic lingo) we can affirm that:

attack(X, Y) ← requires(Y, Z), antonym(Z, X)

The initial hypothesis about John being a professionist can enable the system to make a deductive conclusion in the regards of the abandoned cart. We may say that John is unable to use that camera. Why? Maybe because he does not know that camera. Maybe he does not know the full set of characteristics that device can offer. Again, it is hypothetical yet very plausible argument. What the system can do for him? Well, we have many products in store. One of them is an online course, which is intended for learning, and learning is attacking (for the same principle we’ve seen before) the inability argument. Why not recommend it?

John seems to be caught by our proposal an inspect the course we recommend him. What could be go wrong here? Would be the case John has some reluctancies even for the online course? Maybe John does not have time to attend it, he’s a very busy photographer! But the system elaborates some precious information about the course for prompting some valuable argument to convince John that the recommendation is a valid one. From the description we know the course is just 20 minutes long. For the average of courses on sale this is indeed very short. Let’s tell John he does not have anything to worry about time because the course is short.

Or maybe John is worried by the cost of the course? As inattentive user he might overlooked some important information. No worries John, it is for free!

Comments